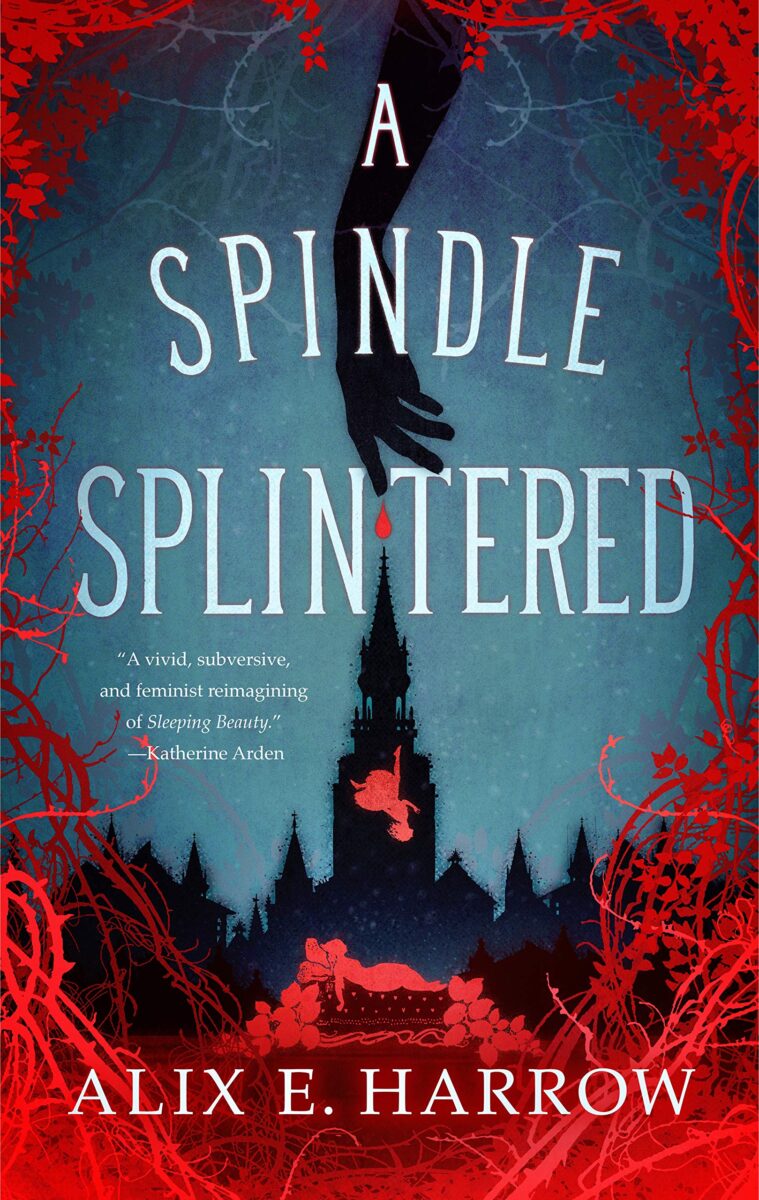

I must shamefacedly admit that A Spindle Splintered is the first book by Alix Harrow that I’ve read, but I can at least say that it certainly won’t be the last. This tiny powerhouse of a book made me a believer, and it started with a fairy tale that Harrow herself points out is “no one’s favorite.”

Sleeping Beauty is Zinnia’s favorite, though. Zin might be a bit of a sucker for lost causes though, being a self-assessed lost cause herself. She has GRM, a (fictional) genetic disorder with a grim prognosis: even with all the medical treatments she can manage, she won’t live much past her 21st birthday. There’s no spindle here (a lot of pills and syringes, but no spindle), but Zin still identifies with the Sleeping Beauty in all her fairy tale permutations. She likes the idea of a nonfatal sleep and the promise of a reawakening.

Her best friend is willing to go along with her obsession, but Charm (short for Charmaine, lest it all be too entirely fantastical) wants to keep Zin in this world as long as possible. She’s studying biochemistry and also doing her damnedest to make sure Zin wants to stick around, which is why she throws her a 21st birthday bash. In a tower (abandoned prison panopticon, but tomayto tomahto) With roses. And an honest-to-god antique spindle.

It’s the best and worst present for the best and worst birthday ever, a celebration of “you made it this far!” to paper over “you won’t make it much further!” And even with this dubiously appealing premise, it goes wrong. It goes wrong to the tune of other worlds and other Beauties, a whole multiverse of girls who are doomed to sleep but who might just want to fight their fates.

A Spindle Splintered spends some time gently poking fun at ’90s fantasy, but it itselfis a fantasy John Green, complete with a snarky dying girl as narrator. The spate of mid-2010s imitators did wear that trope threadbare, but fortunately Harrow has a scattering of good insights into chronic illness, and even better, dying is not the only focus of the narrative. Choices are.

Both Zin and Primrose, her fairytale counterpart, are low on choices. Primrose is the traditional Beauty, her kingdom a hand-wavy jumble of medieval and Victorian scenery that Zin can’t help but criticize for its anachronisms. Not that it matters. The kingdom still functions, Primrose is still cursed, and it’s all going to come to a very pointed (heyyy) end. And even if she somehow resists the spindle’s pull, she’s then doomed to marry a soggy gym sock of a man.

There are unexpectedly heartbreaking moments when the fairy tale falls away and real people emerge from the wreckage. Moments of pure humanity, when people dealt poor cards still gather them up and go, “well, this is what I’ve got to work with.” There’s power in that, and Harrow certainly uses it to dramatic effect for the climax, but there’s also tragedy in the way that stories can entice and then trap us. Sometimes we bow not only under the weight of how our story is “supposed to” go, but also under the weight of love–and expectation–that others place on us. Harrow does a great job of exploring the ways that smothering, overprotective love make you equally (if resentfully) overprotective in return, refusing to get attached as if attachment had a transitive property, and you could thereby help other people not be so attached to you. Zin’s experiences help her find new perspectives and she has a thoroughly satisfying arc–really, one of the better character-driver arcs I’ve read this whole year. It’s completely organic, and driven as much by her flaws as her better qualities.

In forcing Zin (and Primrose) to confront the most typical, amalgamated version of the story, Harrow is also able to find all its pressure points, the spaces where symbols and meaning intersect. These points had very specific implications in their original context, but symbols are mutable. A hero, a damsel, a fairy, a curse–all of these are subject to change. Which also means they’re subject to choice.

Harrow also messes with any number of other features: she makes it modern, makes it gay (and gives us a clever misdirect—I’m looking at you (Prince) Charm(ing)), makes gender and circumstances highly variable, makes timelines fuzzy and locations even less important. Story is all that matters, and because story is a matter of structured choice, it makes for a highly intricate read, one that Harrow is able to tie up in some extremely satisfying ways.

It’s a quick read, too, no more than a solid afternoon or a nice weekend. Harrow packs a lot in, but Zin’s crabby, snarky voice never lets it get too theoretical or abstract. She’s got stuff to do. You should absolutely go find out how she gets it done.