When I was younger, I always wanted a twin. Siblings were fine, but a twin–that would really have been something. Someone just like me who I could always depend on, who would be there to play with and comfort me no matter what. Twins, I believed, were just a little more magical.

Actual twins can tell you that it’s a lot more complicated than that, and that no, they don’t have psychic powers. Fantasy novels don’t really seem to consult them, though. Their fictional magic is usually extreme, and either profoundly symbiotic or diametrically opposed.

Jacqueline and Jillian–Jack and Jill–don’t have any magic powers, unless you consider resisting even a little of their parents’ corrosive expectations to be magic. Which you might. It is a feat. Their mother is a WASP of the highest order, expecting every flounce of girlishness short of actual petticoats (this is modern times, she and we struggle to remember). Their father just wanted a boy–the most boy-ish boy who ever tumbled straight out of Leave it to Beaver and into a Sports Center addiction. In essence, their parents wanted stereotypes and got children instead, and then tried as best they could to force them into those impossible molds anyway.

Deeply damaged even in their tender tweenage years from this constant onslaught of unreasonable expectation, Jack and Jill are not so much siblings anymore as they are two terrible collections of opposite forces ready to unravel–or explode. They orbit one another out of a greater gravity, enviously repelling and attracting one another for all the things they wish they could be. They love each other too, though, and it’s really up to you to decide which is the greater tragedy in the end.

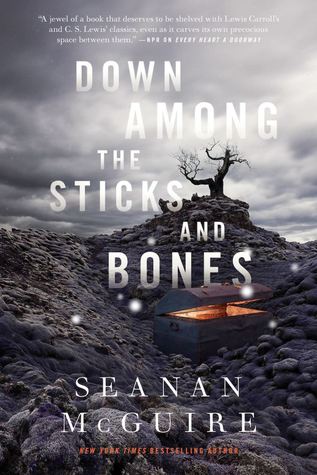

We know what the end is, of course, or at least part of it. This is the follow-up to Every Heart a Doorway, which was wildly successful, especially for a novella. (God bless ebooks.) Jack and Jill were secondary characters in that book, and here we are able to learn the story of how they ended up in another world, their own particular fairyland. Which, in their case, is highly Gothic and contains no actual fairies. Instead there is a vampire of the Stoker variety (not Rice or Meyer, in other words) and a mad scientist who exist in a nervous truce, with a walled town full of ordinary humans between them like a hostage. One twin to one master, one to the other, and a catastrophe waiting for them. But how? McGuire banks on us wanting to know the how of it even though, like Harry from When Harry Met Sally, all of us have morbidly skipped to the end of the book. McGuire has made us morbid, and will make us all the more so by the end. How is it that one twin becomes a killer and the other a savior (of sorts)? How does it all get so backward so fast?

That’s the other twin trope–one evil and the other good. And that’s the other lie that the adults in their lives have forced upon them: that to be one way is to preclude the possibility of being the other. If you are girly, you cannot like sports. If you are a vampire, you cannot care for science. The latter sounds ridiculous, doesn’t it? Well, no more ridiculous than the former. McGuire is exploring what it means to be forced into both gender constructs and a strangely absolute moral universe, when really everything is more complicated than that. Children are more complicated than that, even when their parents won’t let them be.

Our narrator (distinct, I would argue, from the author in this case) is perhaps overfond of telling us this. It is extremely apparent, offering unsolicited explanations in a more-omniscient-than-usual third person, much in the way narrators used to in very early children’s literature. This dry omnipresent voice can get a bit repetitive in its reminders about the twins’ psychology. It wants to make sure we get it. I prefer fewer didactics, but then again, this is echoing those old books that are meant to moralize to their audiences. So ultimately, what can I criticize? It’s a lovely, grim, insightful novella. It’s got love and family and horror and the twisted decisions of imperfect people who are reasonably selfish most of the time.

I very much hope that this return to the terrible wonderlands of the Wayward Children heralds the beginning of a new series, or at least a collection of even more interwoven novellas.

Note: It does. Beneath the Sugar Sky, the third installment, will be out in January!