Note: I don’t think it’s possible to give this book a proper review without at least some spoilers, but since there are several dramatic reveals and—I hesitate to call them “twists” since they’re not at all gimmicky like so many twists are these days—please be forewarned. For people who prefer no spoilers at all, know that I definitely recommend buying and reading this book.

Have you gone? Yes?

Okay. So:

This is not the book you think it is. Oh, sure, lots of books claim that, but this really isn’t. What begins in a city planner’s office starts to get odd around the edges when planner and architect Iona remembers words for things that don’t exist, except in her dreams. But there’s no time for that when a suicide at a funeral shakes Iona far more than strange words ever could. And isn’t it strange that no one else seems shaken at all? Except maybe the king in his tower, but the king is all too willing to be soothed by his chief advisor—a talking cat.

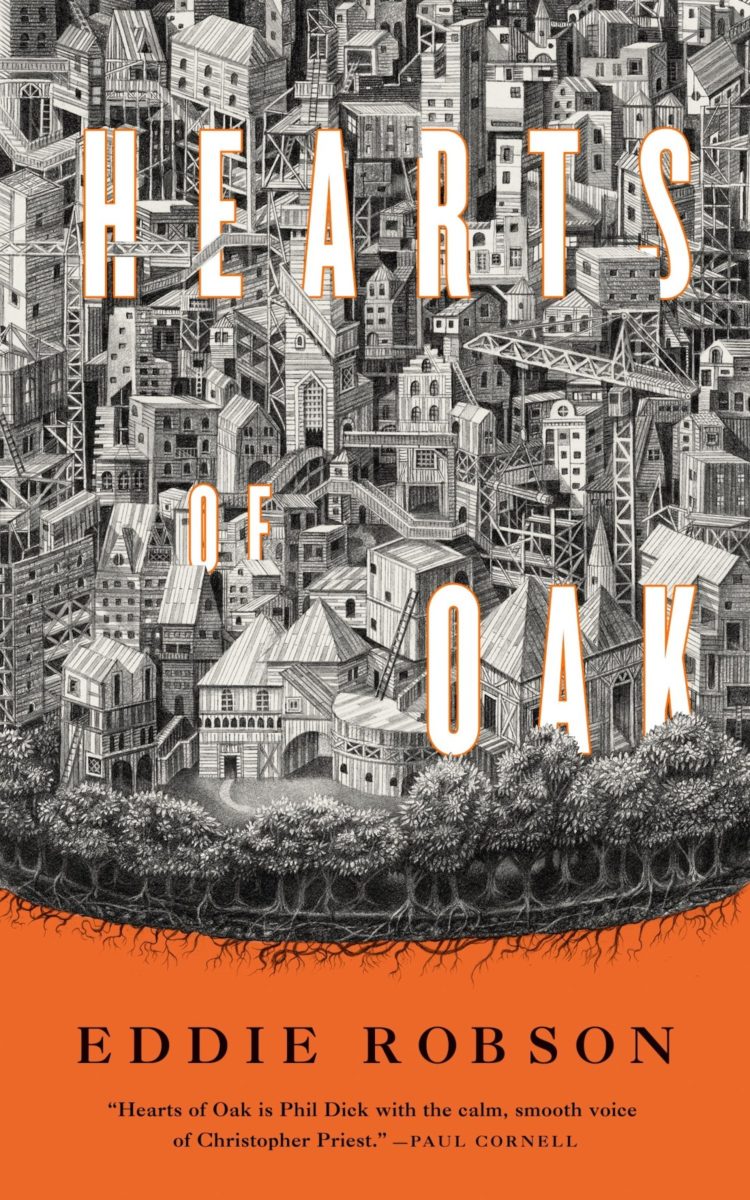

It sounds absurdist, but it goes from surreal to straightforward rather quickly. The questions resolve themselves one after another until we go from an off-kilter Miss Marple to hard sci-fi. Well. Hard might be the wrong word. Because Iona’s whole world (one of her worlds) is made of wood. Including all the automata who inhabit it.

It’s astonishing how much the raw material—imagined material, no less—matters to the overall feel of the story. The material is organic. Everything seems friendlier, more comfortable. It makes the book even more Miss Marple in that the danger and violence seems tidier, less terrible, even a little cozy. Or perhaps it’s a little elvish: a city made from wood seems far more like the serene Riverdell than if the metropolis were made of steel and glass. It’s an unexpected and impressive shift from the SFF standard of gleaming metal and inert plastic. The fact that the robots are made primarily of wood made an incredible difference in the way I perceived the threats, violence, and personalities of the automata. I never could get rid of the idea of wooden dolls, playthings more harmless than not.

They’re not harmless, though. (That would be quite dull, and this book is anything but dull.) Hearts of Oak really gets into the nature of automation, as well as the worth of the work automation produces. There’s immense value in the work that the automata are doing, but that’s partly because the goal they have is real. It has reference to world outside the cage they’re in. But what about Iona? She’s doing the work too, but she doesn’t realize it. All her city planning and her beautiful designs have a certain air of futility once she understands the real reason she’s been building and building.

There’s a question here that no one ever discusses or even really acknowledges until the end: what’s the point? What’s the point of making things beautiful if they’re only going to burn? What’s the point of buildings that nobody needs to live in? What’s the point of making at all?

I don’t think Robson is saying that there’s no point. (After all, he’s literally using a work of art to say all this.) Rather, Hearts of Oak is saying that a few hours of bravery and goodness in reality is better than hundreds of years of creation under false pretenses.

I fundamentally disagree with Hearts of Oak on that point, at least to a certain extent. I don’t think there has to be a larger point to making; or rather, I think beauty is sufficient unto itself. So, for that matter, is knowledge. But I do agree that it’s better if art serves justice, peace, and other noble causes. But I’m all right agreeing to disagree a bit with Robson.

If these arguments aren’t your cup of tea, don’t fret. The book was interested in the questions of what make a life, but didn’t belabor it. The characters didn’t have massive crises of confidence, which I appreciate—it was terribly British how they got on with things. After all, there was a lot to do. Escaping a prison, escaping a planet, dealing with one form of alien life while trying desperately to fend off another, more deadly form…there’s not a lot of time for self-reflection once things get going.

There’s some modern commentary in the nature of the real villain, the species called the Poramutantur, which inhabits people’s bodies and sows every kind of dissent until people start killing each other. What’s particularly interesting about them is that Poramutantur can’t be killed. They can only be contained or banished. It’s a smart—if depressing—take on current events (in that it implies that divisive and cruel ideologies can’t be fully cured, only contained; not that certain world leaders are being mind-controlled). It’s also an intriguing villain for a dramatic sci-fi plot, since it places specific limitations on other characters’ responses.

The characters—Iona, the king, and other who emerge—are equal to the challenge, though.

The ending managed to be sad but fitting, final but ambiguous, and definitely satisfying. Do I have a few unanswered questions? Yes, but the characters whom we follow—Iona and the king—have their storylines resolved. Iona even gets to have a bittersweet triumph after her long—very long—years of moving from the next thing to the next thing, going through the motions. Well, she’s not on autopilot by the end (and those who have read it, forgive the pun). She’s fully engaged with her love, her losses, and the threats she faces. Seeing the world for what it is, and fighting to make it just a little better, is a beautiful finale for her long, meandering life.