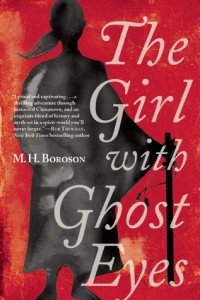

The American West is coming into vogue in a big way. Brandon Sanderson’s getting into it, Rae Carson has a new trilogy set there, and there’s also Vengeance Road, Under a Painted Sky, and Wake of Vultures. It’s an exciting time to be reading all these books, because they’re all so different from each other and so different from what’s come before in this genre. Forget cowboys and injuns, these stories are (for the most part) intent on exploring really new territory. Ex-slaves and biracial Native Americans, women with strange powers and women who seem to have little power at all. And of course Asian-Americans, so often overlooked in American racial narratives. One Chinese girl’s story goes a ways toward fixing that in The Girl with the Ghost Eyes, M. H. Boroson’s terrific debut.

Li-Lin Xian (the titular Girl) is an ordained Daoist practitioner under the tutelage of her father, San Francisco Chinatown’s Master Xian. He keeps the whole Chinese population warded against ghosts, spiritual attacks, and other supernatural malevolences–provided that those citizens are on the up-and-up with the Ansheng Tong, a mafia on par with the ones we’ve all seen from the Italian quarters of New York City. Not quite a gang, but not really a charitable order, the Tong functions as a cultural as well as political authority, keeping customs and order while it makes a profit.

Li-Lin does her best for the Tong and her father, but when trouble comes for her, her father is unable to step in. It’s up to her, a woman cursed with the ability to see spirits, a widow whom everyone knows is doomed to a bad fate, to put a stop to the trouble stalking Chinatown. Possible culprits include a rival gang, a monstrous monk, another Daoist, or even some of her fellow Tong members. The mystery is good, and the magic is even better.

Drawn from extensive research and language study, Boroson has really nailed a lot of the nuances of specifically Chinese “magic,” a word I’m using more as shorthand than because it accurately expresses what Daoists or Li-Lin is doing. Really, Daoist practice consists of a far more complex interplay of textual interpretation (of the Dao De Jing/Tao Te Ching and subsequent texts), physical and mental disciplines, the interplay of folklore, and centuries of tradition, the combination of which is a practice that is loosely called Daoism. Boroson makes so much of this clear without having to resort to overly complex or scholarly explanations. He also doesn’t exoticize this practice, but takes us through Li-Lin’s adventures with some masterful writing and not a small bit of insight.

Some of you keen researchers may have noticed that the author is male and white, while the protagonist is female and Chinese. All I have to say about that is: bravo. Boroson has done his research quite extensively, and he’s approached every aspect of the book with thoughtfulness and respect. No race (or gender) is good or bad, just full of very different people with different ways of doing things. Far from being idealized, Li-Lin and her father have their own prejudices and foibles, just as they have their own strengths. Everyone is so fully realized in this world, so capable and vulnerable. They each have completely understandable motivations, even if those motivations are also simultaneously completely despicable.

I am absolutely ravenous for more of Li-Lin’s story. Though this story wraps up in a satisfyingly bittersweet way, there is so much more room for the continued adventures of Li-Lin and Mr. Eyeball. I mean, she has a spirit sidekick who’s a giant eyeball with tiny arms and legs. How can you not want #sixbooksandamovie? Right, you can’t.