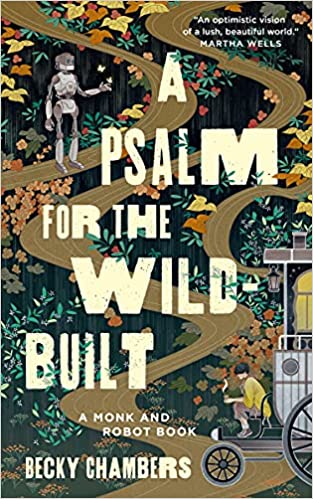

A Psalm for the Wild-Built, the new novella from Becky Chambers, though obviously brief, is a complete meal: it has the rich depth of philosophical reflection, the acid brightness of humor, and the unfamiliar spices of a whole new planet. (Well, moon.) Most of all it is satisfying. This is the kind of book that fills you up.

I may have been hungry when I wrote this, but upon editing I find that my general impression stands: this is a comforting book, the same kind of cozy that Dex themself tries to impart to their visitors. Dex is a tea monk, itinerant but not indigent or celibate. They travel the human lands of Panga dispensing teas that serve as much as gentle herbal remedies as they do enjoyable beverages, but even that isn’t their main vocation. In setting up their traveling teahouse, they also provide a liminal space for people of all kinds to come and share their troubles. Dex is three parts therapist, one part confessor, and two parts bartender. (I’d say barista, but that doesn’t have the right connotations. At any rate, they don’t dispense alcohol but they do provide a pleasant buzz.)

And this works—for a while. But Dex finds themself restless still, longing for an even wider lonesome. They want to hear crickets singing. But crickets only exist in the distant, abandoned parts of the world, places from which humans withdrew as part of a compact with the robots who became sentient many centuries ago. The robots did not want to remain the tools they had been built to be. They wanted to make their own path in the wilderness, and humans—in a shocking triumph of basic decency and wisdom—respected that choice.

We know from the series title and the book jacket that robots are neither gone nor, Dex finds, entirely committed to isolation. Mosscap, a robot from the wilds, has emerged to seek understanding of the human world. “What do people need?” they ask. Dex has asked themself the same question.

I suppose that I should explicitly mention the queerness of the book, which throughout and without preamble has the completely natural use of the third person singular throughout for Dex, who is agender (but, importantly, not asexual—they seem to be bi- or pansexual, if such things even require a label on Panga). Mosscap, the robot, also does not have a gender. This is handled with a lovely, unassuming ease. Acceptance, nonbinary pronouns, done and done.

The whole book is like that, actually: it’s profound and unpretentious, more interested in the big questions and the little moments. It has a lot to say, albeit quietly, about the intersection between aesthetics and enjoyment, or between religion and pleasure.

Pleasure as a tenant of religion is…well, it’s nice to see. Nice, too, is a thoughtful rejection of vocation. Vocation implies that you have important work to do—and therefore, that you must do it. Tying up worth with work is part of the problem I think we’re all having lately, at least in the American experience. But it is enough, says Chambers, to feel. To experience the world, to celebrate consciousness.

Is that truly enough, though, when art is one of the outcomes of vocation? Or a better world? Everything in this world is bespoke, crafted with meticulous care and with the long term in mind. Nothing—and no one—is disposable on Panga. This is a consciously, compassionately made society, which requires everyone’s participation. Dex and Mosscap debate this point, wondering what is necessary. But even this debate is gently undercut by the ultimate thesis of the book, the simple dictate to find the strength to do both (10).

I loved this phrase for its subtle and yet completely obvious meaning, a rich phrase even without the explanation that comes toward the end of the book. Our political discourse is so often painted in absolute terms: yes or no, with or against. Religion, too, is so often pitched as a solution to ambiguity: do this, don’t do that, X good, Y bad. Either/or. Chambers is arguing for both/and. Existence—and perhaps also action.

This conflict actually exists in most of our current religious traditions. A schismatic division between Protestantism and Catholicism rests on the question of deeds: must one perform good works in order to be saved, or is faith the sole necessity? And—Buddhism asks—is being enlightened the end, or ought we seek to enlighten others? The Theraveda and Mahayana traditions have very different answers. Hermits and prophets, churches and sangha. Individuals start religions; communities make them. But sometimes communities become unbearable, and certain individuals retreat once more to solitude. And on and on, the tension between community and individual, mirroring our most primal instincts and wondrous gifts. We are social creatures who survive because of our groups, but our consciousness is absolutely personal.

I’m simplifying, of course. These questions are ancient, the answers complex, and this review obviously won’t answer them (if they even have answers). Even the nature of answering is fraught: should answers be universally applicable, or do they depend on who’s asking? A Psalm for the Wild-Built comes to some preliminary conclusions, but since this is obviously the first of a planned series, it’s not the end of the conversation. And really, the conversation is the whole point. Dex and Mosscap, tea monk and robot, making their way through, sharing tea and their thoughts. What a great way to spend some time, and what great company to keep.