Good horror is scary, but great horror is tender. It does not always speak at a scream, but tells you, very softly but very firmly, what is about to happen. It does not gloat, but likewise does not flinch. It is—inevitable.

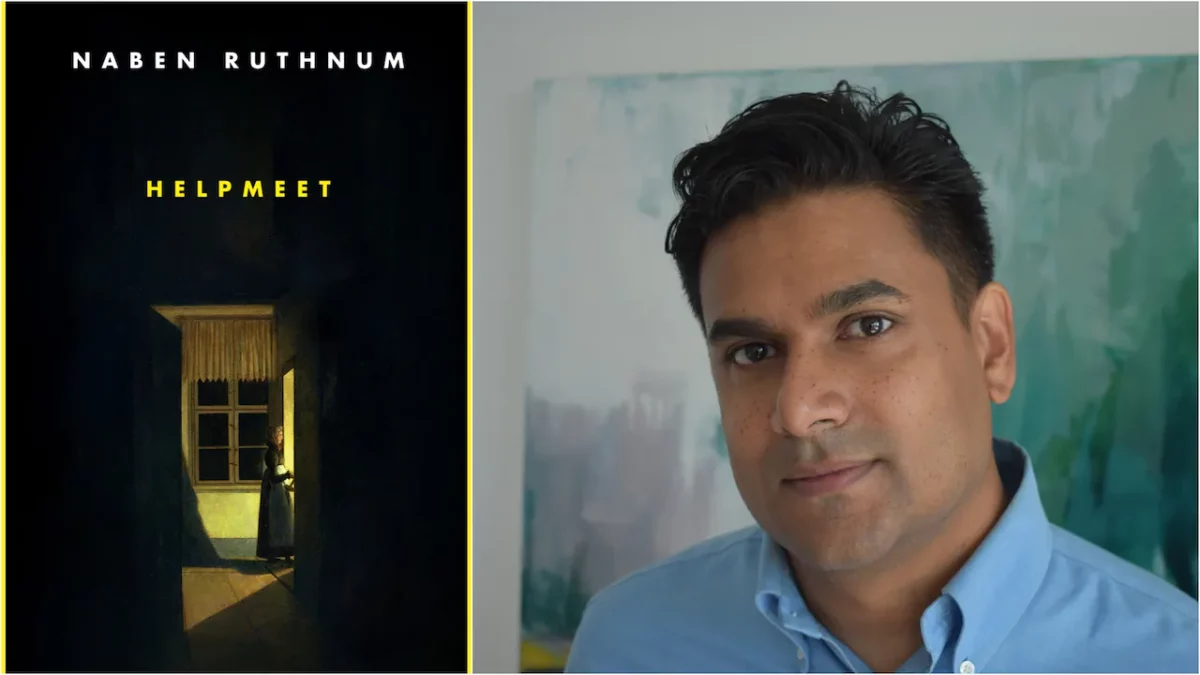

I wish that all novellas were as inevitable as Helpmeet, the exquisite new offering from Naben Ruthnum. From the very first, it neither hesitates nor rushes ahead, assured of its pace. Main character Louise is deliberate in her pace too, taking great care despite the urgency of her situation. She and her beloved husband Edward are planning an escape from New York City to her husband’s upstate ancestral home. They are fleeing their creditors, fleeing the social scene to which they once belonged, but mostly they are fleeing their own helpless resignation. Edward is dying, and he wants to assert his last remaining dregs of autonomy to die in a place he loves.

The weight of all that stress lends Helpmeet a palpable gloom from the very first pages, but this is not a novella that relies solely on atmosphere. There is extensive body horror, too; Edward is dying of an agonizing and disfiguring disease that is all the worse for its uniqueness. Not even the most famous experts have any idea what it could be, which ratchets up the horror as the unknown simmers around the edge of every conversation.

I know it comes from a pet peeve rather than an objective critical measure, but I can’t tell you how relieved I am to find a horror novella in which nobody has hysterics. Yes, sometimes it makes sense for a character to go temporarily insane with fright, but those scenes all quickly feel the same to me, and often smack of To find one set around 1900 is even rarer and even more welcome. People—women especially—can be sensible regardless of the time period, you know! Ruthnum does know. Louise is a former nurse who has lost none of her nerve, nor any of her practical skills. She is familiar with the many ways a body can fail, but her husband is afflicted with a terrible wasting disease that defies her knowledge if not her courage. Experts shudder and shrink away, and so Louise is left alone to invent palliative measures, having long since given up on a cure.

These measures are terrible enough without Ruthnum embellishing them, and he’s smart—he’s brilliant—enough to realize that. He doesn’t even linger over them, trying to squick out the medically sensitive. He, like Louise, just gets on with it. And that reveals the far more awful horror, the kind that can only arise from tenderness: Louise—and the reader—care about Edward. It is not the outward signs of his illness but the inward suffering that makes his pain so horrible to watch. The cracking dryness of his skin, like roasted chicken under a broiler, is bad; to know how it grieves Louise and Edward to see him so diminished and powerless is worse.

Edward is a doctor, or was. His knowledge remains, but his skills as a surgeon are inaccessible to him now, for he has lost his motor control and his sight to a pervasive degenerative disease. There are rumors about the salacious origins of this malady, but the truth, while steeped in crassness, is far stranger.

There is a supernatural element involved that I cannot get into without revealing too much. Suffice to say that it’s surprisingly unprecedented, leaning more toward the cosmic than the spiritualist, which is a nice surprise given the setting. And even this element is oddly tender. There are sympathies in the strangest places, and they incite the horror to an even more piercing conclusion.

Good horror cuts you. Great horror sticks its fingers in the wound.

Or its face.

Want to know what I mean? Read Helpmeet. No matter how unnerved you get, you won’t want to look away.