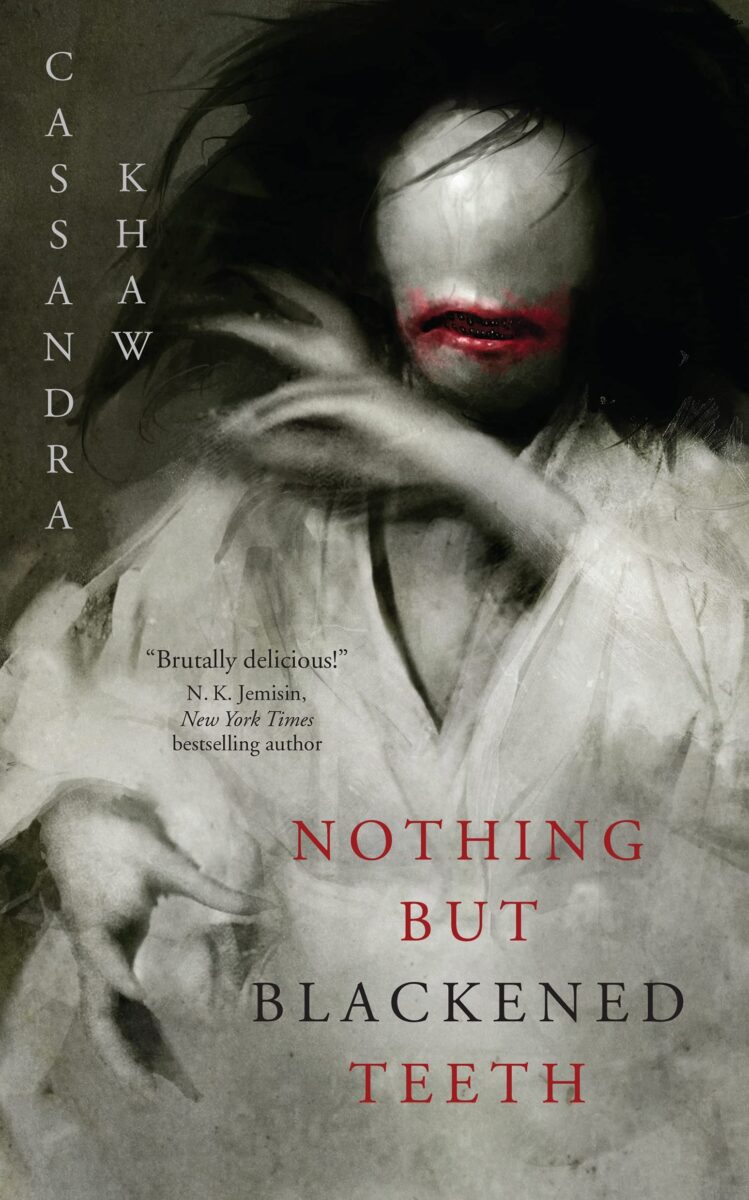

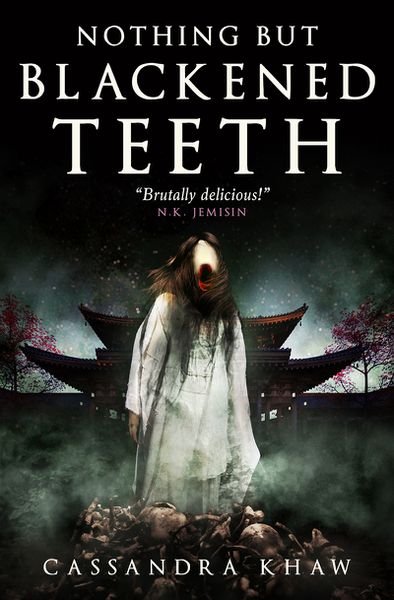

Imagine a mouth full of teeth that are black instead of white. Are you thinking of tooth decay, of weakness and rot? Are you thinking of darkness, the primal kind that lives in a gaping cavemouth or a leech’s maw? Probably you are. That’s a good place to start when you start Nothing But Blackened Teeth, but it won’t be where you end up. Because Cassandra Khaw knows that blackened teeth—which is to say, lacquered teeth—were a mark of wealth and sophistication, an expensive Heian trend. And she wants you to be afraid not of the primal darkness but also of the sophisticated life on top of it, the veneer that makes you think you know what you’re doing and who your friends are. She wants you to know you’re wrong. And she wants you to know that somewhere, there are things that are very, very glad for your distress.

The story may be about black teeth, but Khaw’s writing is exquisitely burnt tongue, which is itself a twisty way of saying that her prose is relentlessly, brilliantly unexpected from first page to last. Every single turn of phrase feels placed, very carefully shaped and then laid next to the one that came before, with the delicacy and deliberation not of a house of cards but of a house of needles. Because the words have wicked points, and Khaw won’t spare you a single jab.

There’s rather more telling than showing in Nothing But Blackened Teeth, which is an interesting choice. It does make dread short-lived and jump scares impossible, since the main character almost always seems to know what’s going on. Instead it cultivates dread, which relies on knowledge and conviction that either don’t help or actively inhibit the characters from fixing their situation. All these friends know too much. They’ve been hunting for ghosts for years, a youthful fixation that is now the only thing that unites them. Their coming together for a celebratory weekend is less kintsugi and more fault lines ready to start bringing everything crashing down. Every one of them has a major problem with each of the others, whether jealousy or resentment or contempt.

There are notes of The Haunting of Hill House here, the instability of the main character and the instability of the core group a nice homage if it was intentional. I am guessing it was. Nothing But Blackened Teeth is very, very aware of the genre, calling out tropes through its characters, who caution each other against being the promiscuous one, the nonwhite one, on how to be the Final Girl. It’s one of Khaw’s ways of problemetizing the larger trends in horror, but not her only way.

Nothing But Blackened Teeth also refuses to let this story be about the horror of the other. This book is about a Japanese ghost in a traditional Japanese house, all firmly on Japanese soil. Cat and her friends are the foreigners here, and their ignorance is part of what causes their problems. I like that there’s no hand-holding, culturally speaking. This is a sparse book that doesn’t pause to remind you that bridal white is an anachronism, that white is traditionally a funeral color in Japan. It doesn’t take a detour to talk about teeth-lacquering, a cosmetic tradition of great refinement dating back centuries. I’m sure there are other things I’m missing, but it’s my job to do the research. Khaw’s only job is to tell the story, as directly and intensely as she can.

As she does. With Khaw tells us about how this strange group of “friends” finally encounters an actual manifestation. Someone is possessed. Someone begins to see things. Someone is convinced beyond all reason that a dark ritual is necessary. All the horror themes are there, and because even the characters are aware of them, they think they’re armored against the worst of what’s to come. They know better than to split the party! They know not to trust their own murderous impulses! They’ll be fine—right?

It’s that smugness, that faith in the idea that lives have narratives, that opens the most space for horror to creep in—because we, too, have certain expectations. The golden boy will be brave, the lovers will be nobly devoted, so on and so forth. But the golden boy actually has a lot of tarnish on him, the lovers have some real issues, and none of them are in a Hollywood movie. They’re in a Japanese ghost story and they don’t know enough about how it goes to follow the narrative threads to safety. They don’t even know enough about themselves or their “friends” to help each other. They can only make it worse.

Cat’s own narrative broke down before the start of the book, when her collection of stressors and traumas became unbearable and she had to check herself into a mental health program. She isn’t sure of what she should be doing anymore, and so she has the easiest time seeing what’s actually going on. Conversely, because she’s had a breakdown, none of the other characters—who think they’re living out the proper progression of love and success and wealth—put much stock in what she’s saying. She’s the Unreliable Narrator!

Nope: it turns out that Khaw is working against the tropes here too, making the “crazy girl” the one actually best able to see what’s going on, rather than the one who slips into axe-wielding madness. Cat knows all too well that stories are the things you tell after the fact, to the police and to the bereaved. You can’t inhabit one; it can only inhabit you.