“The crew of the Rosebud are, currently, and by force of law, a balloon, a goth with a swagger stick, some sort of science aristocrat possibly, a ball of hands, and a swarm of insects.”

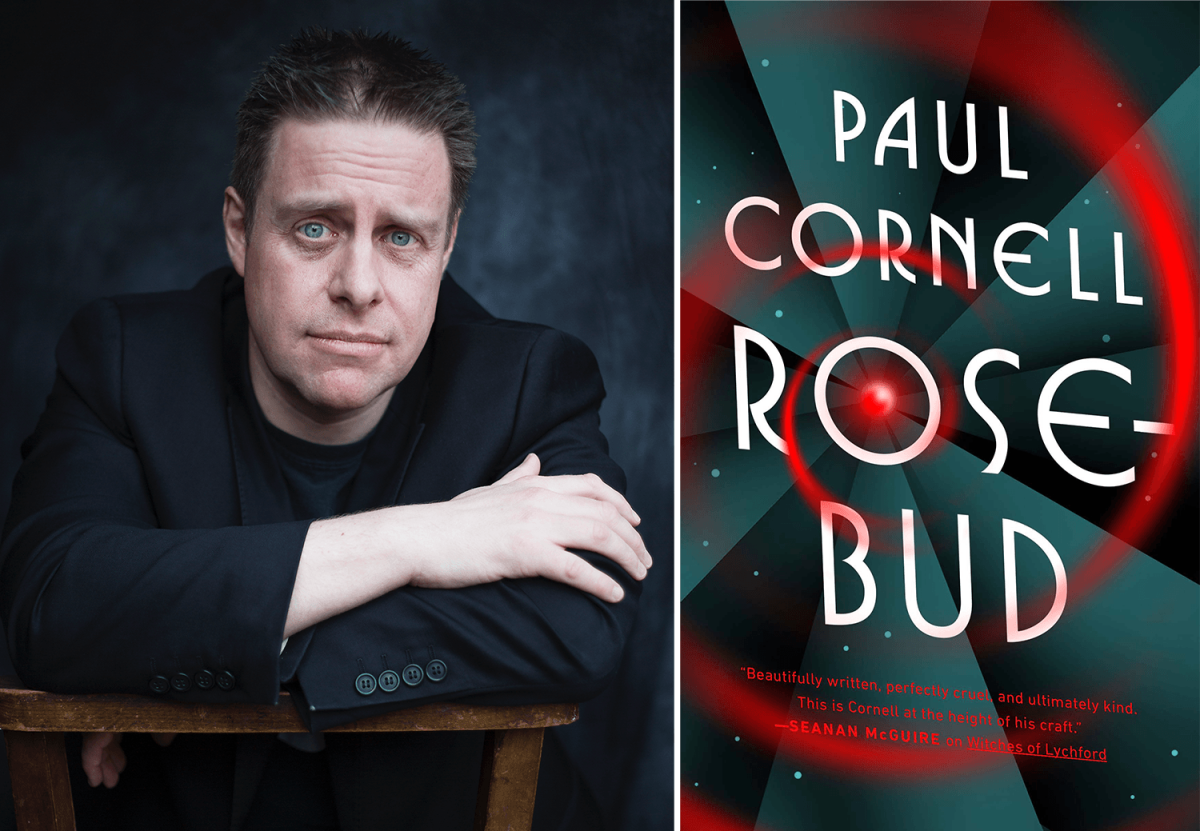

I can’t really improve on that first line and so I’m going to reproduce it for my own review, which can only aspire to the kind of precise critiques and cutting humor that Paul Cornell has so perfected in Rosebud. This novella is a grenade, a huge explosion of ideas and cautions and hopes all crammed into palm-sized story, portable for maximum impact. And the cute covering, the sentient balloon who swears a blue streak and the protagonist space Goth, who broods with self-aware intensity? That’s all the better to draw you in, draw you closer to the vicious, burn-it-all-down fire at Rosebud’s heart.

The five digital crew members of varying appearances and temperaments are not exactly the heroes the universe needs or deserves. They’re a bit bumbling and more than a little fractious, having been crammed into proximity with one another without much regard for their personal preferences. The common uniting factor is that they are outcasts, and despite lacking even a glimmer of other options, are monitored carefully to ensure their obedience. They are complicit in this surveillance, observing and assessing one another without the obvious threat of any panopticon to urge them on. What need is there for a central authority when the power of its attention is pervasive, eternal?

The whole book is, in a way, about observation. Being observed changes the way that both particles and humans act. Humans and other sentient entities, I should say, since the perpetual observation of the Company affects amalgam former-video game AIs like Haunt and hivemind insects like Quin just as much as it does the (formerly) human members of the crew. Everyone on the Rosebud is digital now, and thus subject to the Company’s monitoring and software updates, which keep them enthusiastic about the Company’s definitely, totally, completely benign goals. Benevolent, even. Gosh, isn’t the Company great?

Rosebud is certainly not hiding its critique of big tech, and the horror of a technocracy controlled by a single, all-encompassing entity that supplies necessities in return for unending productivity is not hard to map on to our current moment. However, I appreciate that it’s not Cornell’s main concern. He can do that critique out of the corner of his eye (and ours) while he focuses on the character work and the central mystery.

What is the craft they find, an object so innocuous it raises the hackles of even the most hardy among them? What is it doing out there? In this universe ruled by productivity and profit, it has to be doing something, surely?

The ship they set out to explore ends up throwing wide the doors to their own minds, too, and soon all five of the characters are revealing more to one another in a few hours than they have in a few hundred years. Their wounds are still raw from a long history of transphobic and queer oppression, of the denial of rights to sentient beings, of a laundry list of

The deus ex machina isn’t quite. What I mean is, the whole point of Rosebud is the deus—the novella is about exploring something outside of our whole understanding of time and space that it doesn’t feel like a cheat. And it’s certainly ex machina, a science-based miraculous from some kind of astonishing machine.

Without spoiling too much, I can say that the miracle is probably not what you expect. The solution to humanity’s problems comes from outside humanity, and is put in motion not by our goodness and greatness, but by the abject misery of the most downtrodden among us. Pity saves us, not poetry or democracy or gumption. We destroy the most interesting things about ourselves, and like an exasperated caretaker trying to keep a dog from eating something that will kill them, some great entity must sighingly intervene.

This is a pretty bleak take on the fate of humanity. But it simultaneously leaves you with a sense of hope, too, since a vision of a better future not of our making is still a better future. Both hopeful and despairing, it’s some kind of Schrödinger’s ending. (I probably didn’t use that right. I apologize, physics is not my strong suit. Or even my weak suit—it doesn’t really register as a suit at all, and is more like a card from a different game that’s long since gone out of print.) But I can think of worse things than having a ragtag team of loveable losers stand up for humanity. It sure beats a Company.