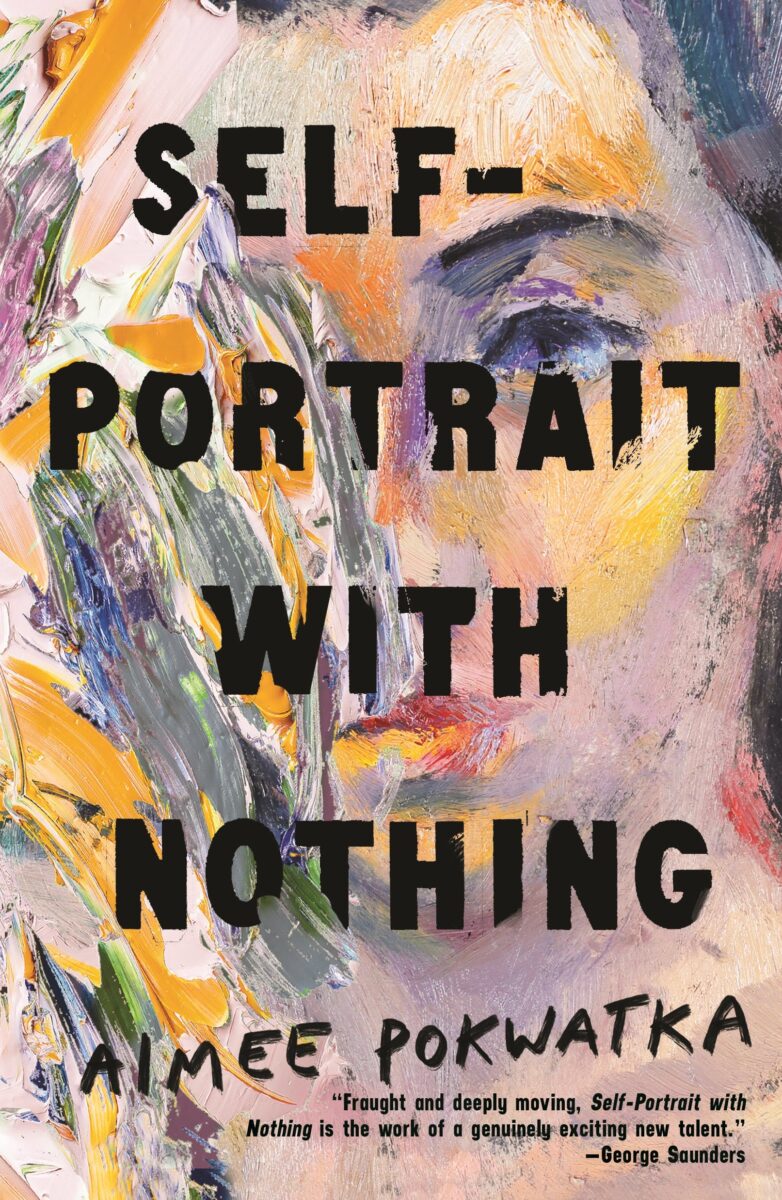

I’ve always felt that visual art should make you feel something first, and secondarily aspire to teach, satirize, or otherwise comment on life. Where that feeling falls on the aesthetic spectrum doesn’t bother me as much—disgust can be a fascinating emotion, just as awe or beauty can—but we have to care before we want to stick around to figure out why we care. It’s a good thing, then, that I cared a lot about Aimee Pokwatka’s protagonist Pepper from the very first. Capable, sensitive, and smart, Pepper is nonetheless plagued by self-doubt arising from the strange circumstances of her birth and adoption. Though Self-Portrait with Nothing is set firmly in the modern day, Pepper was left like a fairytale foundling on her mothers’ doorstep, the only clue to her identity a mysterious coin left alongside her.

Pepper, however, is not the teen heir to a magic kingdom. She’s a professional woman in her 30s working as a forensic anthropologist, and she’s had plenty of time to figure out who her birth mother might be. So when reporters and lawyers start turning up, she’s not surprised when they inform her that her mother is Ula Frost, the famous painter. Ula is an enigmatic force in the art world, commanding exorbitant prices for her portraiture from exclusive clients but otherwise an obsessively private individual. So no one’s quite sure—is Ula Frost dead? Is she missing? Is she just…elsewhere? Pepper stands to inherit both a lot of money and a lot of problems if Ula is gone, and so she sets off to unravel the mystery of Ula, which she both hopes and fears will also be the mystery of who she is—and maybe who she was supposed to be.

Self-Portrait with Nothing isn’t shy about advancing a multiple worlds theory; it’s barely a spoiler. What’s interesting is where the book goes after that, how it pushes the concept into new and interesting spaces. Pokwatka is interested in how individuals would function in a multiverse, how they could begin to see the shapes their lives could take and understand how choices affect outcomes. It’s a nuanced psychological exploration, and it dovetails nicely with the meditations on how art gives us the tools to examine—and sometimes imagine our way out of—our lives, making tangible what sometimes feels hopelessly tangled.

Everything in this book is complex, in a very good way. Pokwatka doesn’t shy from the intricate feelings of adoptees toward their adoptive and biological parents, but doesn’t judge her characters. Likewise, Pepper and her husband have a good, solid marriage, but it isn’t without challenges. The conflicts are character-driven, and the resultant drama feels very realistic for an established couple. Pepper doesn’t need any extra drama, after all. Ula is plenty on her own.

The book itself is functions as a fascinating portrait of Ula Frost, taken at an oblique angle. It’s a bit like A Bar at the Folies-Bergère: the perspective seems head-on but is actually at an angle, and the portrait is more complete than most, providing us with front and back views of the subject—albeit in two parts, divided by the mirror. You don’t have to be an artist or an art historian to fall in love with this book, though; the characters and situations require only feeling, not knowledge. And oh, what a feeling to see Ula reflected through so many perspectives, but remain essentially unknowable. We see her in vivid parts, but we never get her first-person POV, which is definitely the right choice for the novel. She remains ambiguous, almost a villain. Pokwatka never lets her justify herself, because there is no justification for the way she treats Pepper and others. There are only excuses.

Pokwatka clearly doesn’t like Ula—most people, maybe even including Ula, don’t like Ula—but there’s no doubt she’s a compelling character. Her relentless self-interest is not exactly revolutionary—many artists are, or are portrayed as, narcissistic and bonkers—but Pokwatka isn’t asking the normal questions about what artists must do for the sake of their art—the perennial debate of whether suffering is the necessary foundation for genius. Instead, she asks what the toll of art is on others, and whether that can ever be worth it. Who does art serve, in the end? The artist? The viewer? Itself?

While pursuing her mother across borders and through various questionable activities, Pepper has to come to grips with what art can and cannot do for her just as she has to grapple with what her birth mother can and cannot give her. Given the urgency of the mystery, Pokwatka has a remarkable ability to give Pepper the breathing room to reflect while not letting the action falter. Part of this has to do with Pokwatka’s narrative approach. When Pepper is tired, Pokwatka gives us impressionistic portrait “sketches” of what she sees, the people passing on the street and the salient details of their expressions or outfits. It’s a very effective way to establish scene and mood while also functioning as an ongoing nod to the visual art world, a world (and worldview) that Pepper shares with her biological mother whether she likes it or not. Pokwatka is clever but not smug about this technique, never calling too much attention to it, and it works like a charm.

Pepper’s journey made for a compelling, compulsive read with a surprisingly deep story that lingered long after I finished. Self-Portrait with Nothing is a rich, layered composition with many themes and a strong central focus, full of imagery you won’t soon forget.