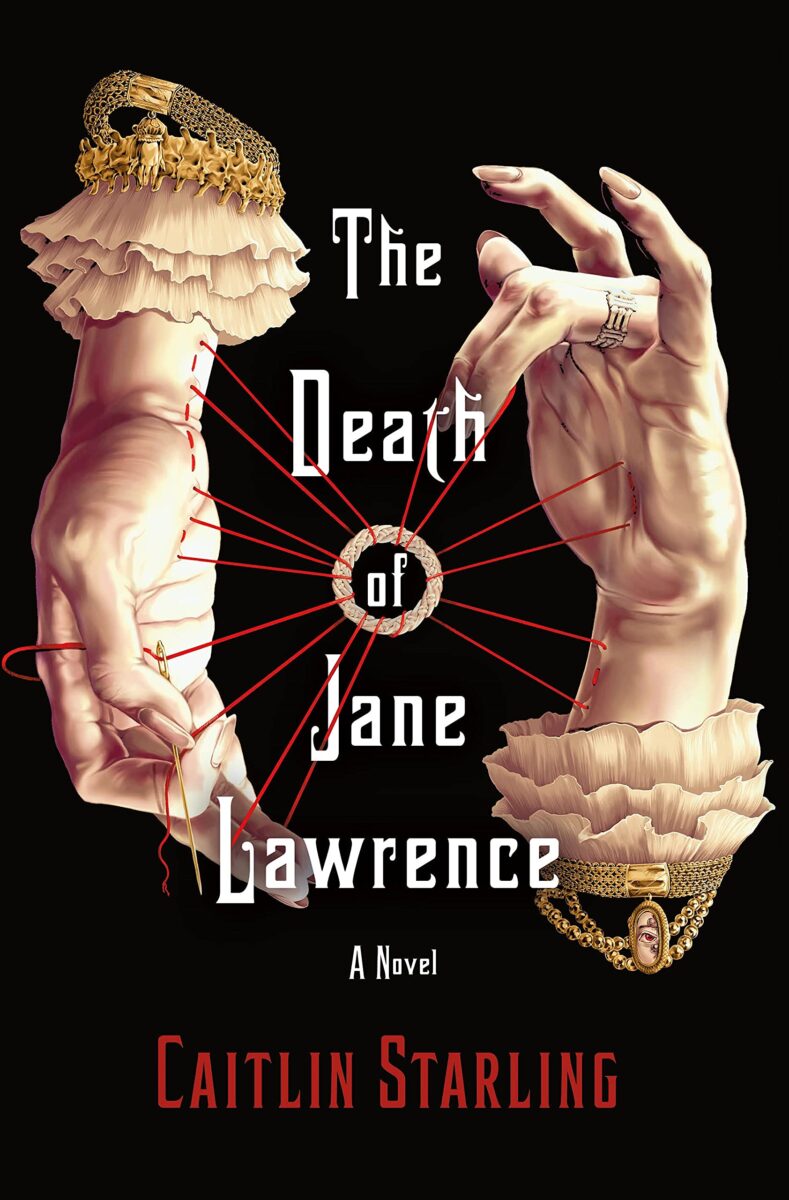

I only meant to start this book. I did. And then suddenly it was way too late at night and I was several hundred pages deep, reading the same paragraph three times because I was falling asleep but not even mad about it. Reading Caitlin Starling’s prose is a pleasure no many how many times you encounter it, and making even one more paragraph of progress through this twisty terror of a story was sheer fearful delight.

Jane is a marvelous main character, and from the very beginning I loved her big, messy heart. She longs for human connection but struggles with social interaction; she wants to be useful, to contribute in the ways she knows she can; she’s curious, clever, and kind. She’s written as autistic , although her world has no word for it(the subtext is very clear, and the author has also explicitly stated it). Jane is seeking a marriage of convenience, one in which she can barter her accounting and management skills for a financially supportive relationship so that she no longer needs to rely on her guardians. After careful research into suitable candidates, she makes this unorthodox “proposal” to bachelor Dr. Augustine Lawrence.

Obviously the book is called The Death of Jane Lawrence, so it’s no spoiler to say what happens next. What I didn’t expect was the phenomenal romance that blossomed from almost the first. I’m so glad Starling managed to find the middle ground between slow burn and sanity. Her characters are rational adults with many interests and priorities, so the romance doesn’t overwhelm the larger narrative or turn the characters into gibbering dimwits. Jane and Augustine are people first and would-be lovers second, their interior lives rich and complex with or without their growing affections. Also fortunately, Starling manages to nail that Victorian ability to make the touch of a hand or a relatively chaste kiss seem as electric (and sometimes downright pornographic) as a sex scene. The romantic tension actually enhances all the dramatic tension, making The Death of Jane Lawrence all the more effective.

For horror and SFF fans, there are also a number of pretty great fake-outs. Not big intentional ones, but if you’re familiar with the genre conceits, don’t worry: you may fear you know exactly where things are going, but you don’t. Dr. Augustine Lawrence isn’t going to turn into some lurid, predictable Hollywood monster. Jane isn’t going to turn into some fainting victim. The monsters and entities aren’t what they seem, either, and Starling takes some unorthodox twists and turns to destabilize our expectations.

The mansion to which Dr. Lawrence is heir is, inevitably, haunted. Strange figures appear in reflections at Lindridge Hall, the cellar is padlocked for no discernible reason, and the servants whisper about strange goings-on. All the Gothic hallmarks are in place for Jane to find, but once she does, she takes the story in an entirely different direction. She is no Mina Harker or Elizabeth Frankenstein, her life dependent on her husband’s courage. Instead, when threatened by the supernatural, she embraces it nearly from the first. She’s curious, and she knows that her logic is as powerful as any madness creeping up from the basement.

I love this concept, and I’m torn about critiquing an aspect of The Death of Jane Lawrence that’s in keeping with the genre conventions, but that as a modern reader I nonetheless find somewhat outdated and ineffective. Gothic literature is deliberately lurid with madness and hysterics, and with supernatural entities that prey on both mind and body. Overreaction—or let’s say hyperreaction—is a pillar of the genre, and I don’t want to fault Starling for leaning into it.

However, I’m going to err on the side of critique not only because it eventually affected my reading experience, but also because it gradually made me frustrated with Jane. I found her ceaseless edge-of-sanity anxiety wearying rather than suspenseful after a certain point. Jane took it to 11 every time anything happened, and not only did I eventually run out of the energy to keep up with her, I began to wonder why she didn’t become inured to her circumstances like I had. After the first few ghosts show up in a house that absolutely everyone agrees is haunted, wouldn’t you take it a little more in stride? But instead, her terrors became one-note, all her complexity flattened by fear. I’m not criticizing her emotions; I’m only criticizing the extent to which they take over her narrative, rendering her less and less recognizable as the character I so swiftly loved in the beginning.

This isn’t to say that Jane is reduced to some puddle of weeping. She’s still able to react, to plan, to try to get ahead of the forces that are tormenting her. She’s clever and determined, and she eventually reasserts her rationality against every mad challenge thrown at her. It’s that quiet moxie that won me back over after a somewhat confused middle section. Jane stopped doing and believing as others expected her to, and instead . The ending actually requires you to embrace Jane’s perspective as well, if you want to have any hope of understanding the details of what really happened at Lindridge Hall. And that to me is a final clever turn in a book full of them: that Jane should not be brought around to strange traditions and standard beliefs, but that all of us should find ourselves required to remake our whole understanding into what she knows to be true.