Can the deliberate, repeated, and visceral slaughter of intimate partners be charming? I don’t think I’m allowed to say that, but after reading Walking Practice, I can’t help it. Perhaps better to say I’m charmed, safely in the past tense, by the wacky, brutal, and ultimately highly relatable tale of an alien trying to survive on our strange little planet.

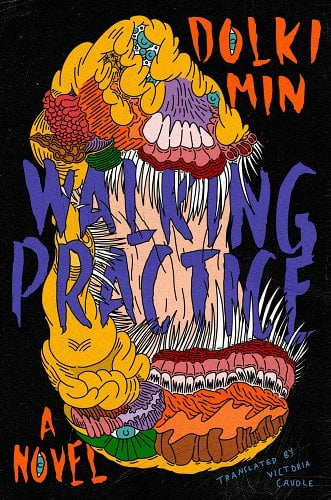

Walking Practice is the debut novel from Korean author Dolki Min, translated by Victoria Caudle after serendipitously being given the book. I’m so grateful for that chance connection, because it gave me a chance to meet Mumu, the mesmerizing narrator who invites us to hear their tale of survival in a world hostile to their basic needs—a story that happens to involve heaps of casual sex, murder, and…yes, walking.

Like most others they encounter in the city, Mumu trudges through the streets and subways with barely enough energy to make it through the day. But unlike regular commuters, Mumu isn’t beaten down by a job or family—they are from a planet with much lower gravity, and are therefore constantly weighted down. The struggle simply to ascend the subway stairs is palpable and compelling to anyone who has ever hated their commute, and the relatability doesn’t stop there. Mumu is by turns maudlin with despair and giddy with delight over simple successes or setbacks, their off-kilter perspective infusing everyday life with a fresh jolt of interest.

Mumu is searching for true connection in a world that forces them to hide their true nature. They want intimacy with others, but the best they can manage is a rotating cast of hookups. Attempts to divulge their true nature are met by disbelief, and any requests to accommodate their weakened, fragile body are met with cold indifference. Their sexual partners treat them mostly like a body, and so it’s not entirely upsetting when Mumu does the same in return.

Mumu takes a Lecter-esque pleasure in the preparation and consumption of human flesh, although in their case, the drive is not a twisted psychology but a biological necessity. They tried everything else, but only human meat will sustain them. Preferably when seasoned well and expertly seared, but raw or dried into jerky will do just fine in a pinch.

Mumu sometimes refers to humans as meat, but this isn’t a psychopath’s trick to render victims less human. There’s no point in dehumanizing prey when you yourself aren’t human, for one, but more than that, Mumu often experiences their own body as a separate from their consciousness as well. Sometimes they loathe their body, which torments them with its difference and its poor adaptation. Other times they coddle and praise it, celebrating how it can feel pleasure despite the existentially bleak circumstances. Either way, Mumu separates their consciousness from it, an arm’s length distance that underscores how alienated (heh) everyone has become from their physical existence.

This is, of course, a deeply queer story. Mumu feels and is made to feel perpetually different, doesn’t understand arbitrary cultural expectations, and struggles to be understood. They face extreme violence, fear, and shunning, all while fighting the whole atmosphere simply in order to move about their life. They don’t want to be human; they must, however, pretend. Though a fine-looking specimen of their own species, they have been made to feel monstrous and feel constantly forced to conform, especially when it comes to gender. Mumu doesn’t have a human gender, although they can adopt one by a painful, intensive process of shapeshifting. In their true form, they’re profusely hermaphroditic, with multiple penetrating and receptive sex organs and ample ability to reproduce, if should they encounter another of their kind ever again.

There’s a big emphasis on the if. While they don’t entirely despair of this possibility, Mumu doesn’t have high hopes. After escaping a catastrophe and crash-landing on earth, they have no means of communication or return. They’ve been alone for more than a decade, a period of extreme loneliness made worse by the fact that their lifespan is quadruple that of a human. They are staring down centuries of loneliness and longing punctuated only by casual sex and intrusive human meddling, whether that means rude stares, unwelcome personal questions, or outright groping on the subway. Mumu doesn’t stand for most of this, and there are several memorable scenes of well-deserved comeuppance for the perpetrators. But vengeance and hookups are no substitution for emotional connection, something we begin to feel keenly alongside Mumu all too quickly. Mumu’s search for genuine understanding makes for a bizarrely poignant little novel, one that I devoured (pun intended) even with the slight difficulty in navigating the spaced-out text (for those reading the ebook: no, it’s not a formatting issue). It has a lot to say about the absurdity of the human condition, and all its wonderful, horrible weirdness. All this is to say, go buy Walking Practice immediately. And then shelve it next to A Certain Hunger if you’re inclined to its macabre side, but just know that, with its sly absurdity and sheer delight in the transgressive, it fits equally well in the company of The Hitchhiker’s Guide to the Galaxy.