I confess that I had never read “The Fall of the House of Usher” until What Moves the Dead came out. (Other Poe, yes, but I prefer his poetry.) But I could not in good conscience review this novel without reading the story it is directly and explicitly commenting upon, and so to The Collected Works I went. I found, just like T. Kingfisher noted in her acknowledgements, that it was actually quite a bit shorter than expected. It looms large in culture, but it’s very short indeed, and to my even greater surprise, it’s literally about a fall. Poe wasn’t being poetic there: the actual house falls down. Quoth the reviewer: wait, what now?

Of course, it’s also about the end of a family, and about several of the usual Poe obsessions, mostly nervous affliction and gloom. The whole story is one of atmosphere rather than plot, and so it’s no surprise that it changes quite a bit in the hands of someone who is more focused on plot and character.

Speaking of character: other than a few mentions of their long acquaintance, Poe’s story gives us little reason to sympathize with Roderick Usher, and no reason at all to see Madeline as anything more than a tragic ornament of the creepy house. Both of them are weak but wild, madness lending a certain terrible appeal to their last dark days. Doomed beauty is another of Poe’s fascinations—but it’s not Kingfisher’s thing at all.

Kingfisher has a clearly-established affection for sensible people. Even if their hobbies or their choices are unusual or actively dangerous, she likes people who ask the basic questions and run away at the appropriate times. Hence the previously unnamed narrator of the short story gets a name in What Moves the Dead, and a personality besides. Alex Easton, an officer and childhood friend of the Ushers, arrives at the gloomy estate and kicks off the story. Alex and Roderick served in the war together, but he was not drawn back into contact by their mutual ghosts. Instead it is Madeline who spurs Alex’s visit, having written Alex a letter so disturbing that ka had no choice but to go to her side.

A note on the pronouns: Alex is a sworn soldier of the fictional country Gallacia, and uses the neopronouns ka/kan, which specifically refer to anyone serving in the Gallacian military regardless of previous identification. Gallacia has several other extremely useful pronouns, including one that I would certainly like to hear more about that is for “rocks and God.” But to return to the point: Alex encounters some early difficulty explaining kan sworn status to Dr. Denton, an American who has witnessed a bit more of the Ushers’ decline. He is at a loss to explain their feverish temperaments and odd behavior, and so he and Alex can largely only wait for the inevitable.

What works: the pacing, the characters, the worldbuilding,

What doesn’t: could be subtler leading to reveal

Ideal reader: fans of Poe, Mexican Gothic, or Area X, anyone who likes creeping dread, anyone looking to get lost in a book

But what, exactly, is inevitable? Alex is perplexed that the Ushers will not leave their miserable home for a more hospitable climate, since it’s clear the moldering walls and grimy passageways are contributing to Madeline’s illness. Their genteel poverty cannot keep up with the decay, but is it more than pride that keeps them at their family’s estate? In trying to understand the hold it has over then, Alex tries to learn more about the countryside, only to find even stranger things creeping across the moors. Kan training and steely resolve may not be enough to fight dangers too huge to comprehend and yet too subtle to be seen, but ka will try.

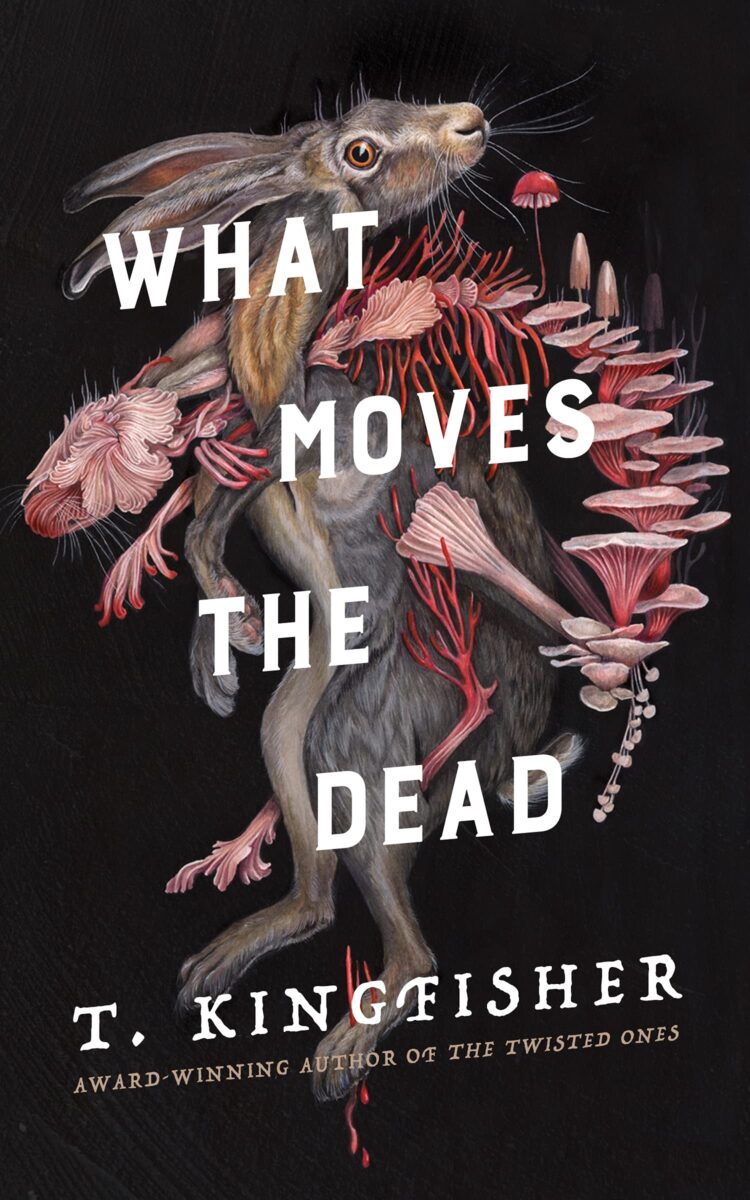

What Moves the Dead is not the scariest of Kingfisher’s work. That honor belongs to The Hollow Places, or perhaps The Twisted Ones. Instead it’s persistently unnerving, perhaps taking a note or two from Jeff VanderMeer’s Authority with its infestation of uncanny hares. Later revelations were no surprise, not with that opening chapter and not with any knowledge of the original short story. Fortunately, the book is not relying on my least favorite trope, the twist. Instead, Kingfisher builds an atmosphere of dread quite literally from the ground up. You will be afraid of the earth. You will be afraid of the air. You will be afraid of the water. You will, in short, be kept reading by your fearful certainties that something is certainly amiss, and that possibly everything is very wrong.

The pacing is a perfect complement to this creeping dread, feeding out just enough information and action to maintain the perfect state of anticipation. Anyone worried from the first chapter that Kingfisher will veer too hard into adopting 1890’s style need not worry. There is a loose adherence to phrasing and attitudes, but Kingfisher’s trademark humor and forthrightness remain intact, and drive character development forward as well.

There’s so much forward motion in this book that I finished it in two breathless days, eyes glued to the page at every opportunity. Horror fans, Kingfisher followers, and Poe aficionados will all find something to love in What Moves the Dead—and more importantly, will find something to make them shiver.