It’s often said that it’s not the destination that matters, but the journey. Just so with today’s game, Tokaido, a recent (2013) offering from designer Antoine Bauza—he of Ghost Stories, Hanabi, and 7 Wonders fame. Tokaido is a very different game from Bauza’s other works, not least because of its unusual inspiration: the legendary Tokaido road, which spans some 500km of the southern coast of Honshu, from Kyoto to Edo (that is, modern-day Tokyo).

It’s often said that it’s not the destination that matters, but the journey. Just so with today’s game, Tokaido, a recent (2013) offering from designer Antoine Bauza—he of Ghost Stories, Hanabi, and 7 Wonders fame. Tokaido is a very different game from Bauza’s other works, not least because of its unusual inspiration: the legendary Tokaido road, which spans some 500km of the southern coast of Honshu, from Kyoto to Edo (that is, modern-day Tokyo).

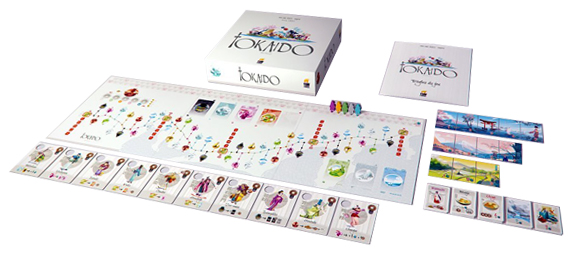

That journey is represented via a long chain of spaces on the game board. Each one represents a place that a pilgrim might stop at along the way: a Village, a scenic Panorama, a Temple, or a chance Encounter with another traveler on the road. Players compete to have the most enriching journey, accruing victory points as they visit particular spaces along the way. Only one player can occupy each individual space, but the types repeat as the road progresses, so players get multiple chances at each type over the course of the game. (In a four- or five-player game, some spaces allow two players at once.)

That journey is represented via a long chain of spaces on the game board. Each one represents a place that a pilgrim might stop at along the way: a Village, a scenic Panorama, a Temple, or a chance Encounter with another traveler on the road. Players compete to have the most enriching journey, accruing victory points as they visit particular spaces along the way. Only one player can occupy each individual space, but the types repeat as the road progresses, so players get multiple chances at each type over the course of the game. (In a four- or five-player game, some spaces allow two players at once.)

Some spaces give an immediate benefit: a few coins for a stop at a Farm, a few free points for a soak in a Hot Spring. More commonly, though, spaces give players chances to assemble various sets of cards to score points. They might stop to paint one section of a multi-part landscape panorama, for example, or they might buy souvenirs at a village, trying to collect exactly one of each type of gift to score points. These combinations can be rewarding, but they come at the cost of requiring multiple stops at specific types of spaces along the road.

Panoramas are three, four, or five segments total—each additional piece scores progressively more points.

The strategy, then, arises from trying to visit the most and best spots yourself, while blocking other players from visiting the places they need to complete their own combinations. In this regard, Tokaido plays out like a very lightweight worker-placement game: you have to take into account what your opponents will value, to find spots that they might skip over or to block spots they really want.

All this jostling for position is managed by Tokaido’s elegant movement mechanic. Players can move as far ahead as they like to snag a valuable spot. But doing so means they’ll miss spaces along the way, and, even worse, give more opportunities to their opponents: you can’t move backward, and the player at the end of the line is always the next to move, so you might leave your opponents with multiple moves in a row if you rush ahead too quickly.

Purple moves next, and can move as far ahead as he likes. After Purple, Green will be last in line, and next to move.

Pacing the journey are the special Inn spaces at the one-quarter, one-half, and three-quarter marks. Inns force players to wait up for the rest of the group—no one can move past the Inn until all players have arrived. They also give players the opportunity to purchase meals, which are the highest-scoring cards in the game. There’s a clever tension built in here as well: the early players get their choice of the best remaining meals, but the later players move first onto the next segment of road.

All this seems like a lot to hold in one’s head, but the game play is simple and straightforward: go to a spot, do a thing, let someone else move. Your first game will breeze by as you practice moving and check out the different square types. It’s only later, as you begin to strategize your moves around your fellow players’ moves, that the game shows its real complexity.

But, refreshingly, the challenge of Tokaido comes from other players themselves—it’s not solving a math equation, which so often is my friends’ complaints about games like Caylus. Instead, Tokaido is a little ballet: brightly colored pawns sliding past one another on a gorgeous, minimalistic game board, all dancing inevitably toward the end of their shared journey.

Oh, a word about that game board and that gorgeousness: the visual aesthetics in Tokaido are absolutely phenomenal. The board and game cards have an attractive simplicity to them, which pulls focus to the beautiful illustrations by artist Naïade. The art depicts a nonspecific Edo-period Japan. Taken together, the visual appeal reinforces the sense of contemplation, serenity, and personal growth the game takes as its flavor inspiration. This is one of the few games I can remember where the artist is credited on the front of the box next to the game designer, and it’s eminently deserved.

To make sure each trip down the Tokaido is different, players also take one of ten personas as their avatar for the game. Each character has his or her own particular allotment of starting cash and a unique special ability, usually one which encourages the player to emphasize a particular type of space more than others. For example, Mitsukuni the Old Man earns extra points for visiting Hot Springs, while Sasayakko the Geisha receives some of her souvenirs for free.

These character tiles are good additions, since I do have some doubts about the replayability of the game. It’s not that successive plays are uninteresting: since the challenge lies in discerning what’s important to your opponents and weighing that against your own priorities, each time you play with a different group, you get a different game. It’s more that the first games are such enjoyable journeys of discovery that later games, which focus more on strategic movements and blocking opponents, feel notably less transcendent. Playing with different characters helps keep those choices feeling fresh, as each character encourages you to seek different strategies.

That said, adding more opponents also changed how the game played; with two or three, the choices were more straightforward and it felt like players could better focus on particular strategies: all panoramas, for example, or all souvenirs. With five players, our group moved as an intricate little knot, and the choices were more complex and interesting.

In the end, Tokaido is definitely a must-play. The game also seems well worth owning—not only will you want to display it proudly from a prominent shelf, it should stay fun for a number of plays, and is especially good for friends who are new to board games or who prefer ones that are less “crunchy.”

Tokaido is produced by Fun Forge games with an MSRP of $39.99 (click here to buy on amazon). The game has one expansion, Tokaido: Crossroads, which adds six new characters and several new object types. (I haven’t yet played the expansion, but it looks good.)