One of the most common ways to build a fantasy setting is to base it on some certain aspect of the real world and then make as many–or as few–tweaks as possible. For a long time, all we got were variations on medieval England. Then, slowly, other times and cultures began to trickle in. We’re a ways away from true parity, but diversity is improving, and we’re starting to see fantasy worlds based on entirely different civilizations.

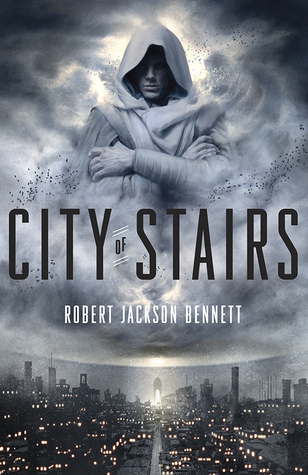

What’s really impressive about City of Stairs is that it nods to Eastern Europe, Scandinavia, and India on the way to creating something entirely removed from all of them. Bulikov, the eponymous city of stairs, is overflowing with saints and heroes and gods, but none of them bear much resemblance to this-worldly religions. And yet they have that epic quality to them, the kind that many less confident writers have to crib directly from our own pantheons. The myths are fully fleshed–sometimes a little too literally, as many unfortunate characters find before long.

The murder of a noted historian, whose postmodern Dumbledorisms are relayed via his notes and essays, has plunged the city into chaos. Residents variously resented or outright hated him because of his access to their sacred history; his fellow Saypuris certainly didn’t need the trouble he was causing; and history itself, always restless in a city of magic, may not have been entirely innocent either. Enter Shara, a secret agent of Saypur but also a scholar of the continent. Her deep love for both countries sets her down some very strange paths in pursuit of the murderer, along with her faithful “secretary” Sigrud.

There’s something quite archetypal about Shara and Sigrud. The slight, calculating, glasses-sporting spy and her juggernaut of a “secretary” are a match made in heaven, not just for the ways that their skills complement one another, but in the way that their relationship is so delightfully easy. Despite their physical, cultural, and political differences, they are on exactly the same wavelength. Thankfully, there’s no hint of romance. It’s so much easier this way to appreciate their complex history.

It’s easy to appreciate the other relationships that populate the book. As befits a book about a spy, none are straightforward, but all are compelling in their complexity. Ex-lovers, ex-warriors, ex-kings, and ex-gods–all kinds of people in transition from one state to another, never sure where they stand in relation to the world and each other. It’s a precarious network of people, and the best part is, they’re all trying to do the right thing–they just don’t agree on what that is.

Vohannes, one of the many exes in several sense of the term, is particularly well-drawn, wry and devious and delightful without being a caricature. There is a speech Vo gives that was so beautifully defiant and insightful that, if it hadn’t been five in the morning, I would have stood up and clapped. Yes, this is the kind of book that keeps you up, with its excellent prose further elevating the layers of mystery and action sequences and mythology.

There are also some nuanced meditations on colonialism that never descend into preachiness–Bennett’s world is too complex for black and white moralizing. Instead characters grapple with the grittier, more personal implications of imperial politics. Can you hate your oppressors but still value some of their views? Can you work with them if it means bringing prosperity to your people? And for the colonizers themselves, is it possible to be benevolent overlords? What even constitutes benevolence? And most importantly, who has the rights to history?

I would have greatly appreciated a map to have a better sense of the cities, provinces, and countries involved. Perhaps the next book, which promises to feature the salty, foulmouthed Turyin Mulaghesh, will include one. I am eagerly awaiting its release (along with so many other books slated for early next year…basically, don’t talk to me from November through January). Until then, I recommend savoring the ascents and descents through the City of Stairs.