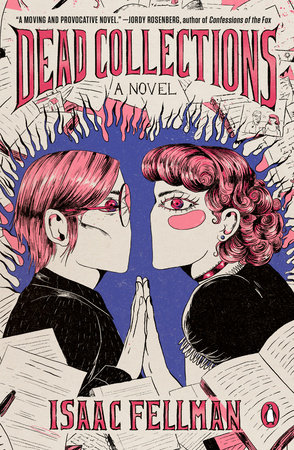

Being alive, my grandfather always said, is not for cowards. Neither is being dead, according to Isaac Fellman, who in his sophomore novel Dead Collections explores the life of a vampire struggling to reconcile the life he wants with the life he has. It’s a thoughtful and, yes, profound examination of vampires: their mythos, their pathos, and their queerness. It’s also a meditation on how that queerness can exist in the world, insisting on permanence when the very nature of death and undeath are constantly trying to bury what the living world has not managed to erase.

Sol Katz was deliberately infected with vampirism in order to save his life, but his life has become anything but lively since then. His gender transition has stalled because of vampiric stasis, his social life has evaporated, and he’s not-so-secretly living in his office in the Historical Society of Northern California archives. He consoles himself with fiction but sustains himself with fact–his job is curating archives, tending to the physical realities of other dead folks. One such dead person–and the catalyst for the story–is Tracy Britton, who created Sol’s favorite show. But before he can engage with the living Tracy he’ll have to find life for himself. Sol is existing more than living when Dead Collections begins, clinging to sustenance and shelter and work as proxies for real engagement with his vulnerabilities.

In most fantasy, a vampire’s vulnerabilities exist to be exploited. Garlic and silver and sunlight are for the heroes; flavor and wealth and beauty, in other words, are not for the undead. For those who are different. Nor, I might add, is holiness, although crosses don’t do anything to Sol, not as a vampire and not as a person, since he’s Jewish. Garlic and silver never come up, either, but sunlight, that’s Sol’s most persistent enemy in a life full of fresh dangers, and one among many for which there is precious little protection. There are vampire clinics and vampire experts, but as with other rare diseases, vampirism is still insufficiently studied and underfunded. It’s impossible not to draw parallels with HIV/AIDS as Sol receives infected blood (to which vampires are immune), and as he struggles with hiding his symptoms. And when he tries to find consolation with a support group, he’s beaten for his single slip-up when they realize he’s drunk blood directly from a living person, risking spreading his infection.

This incident also brings up interesting questions of risk and consent. What are we allowed to risk in our quest for fulfillment, and what can we allow others to risk on our behalf? When our hungers are entirely natural but potentially deadly, how do we reconcile ourselves to the world?

It ought to be: how should the world reconcile itself to those who are different? But that’s not how it is, unfortunately. Because the vampirism isn’t just a metaphor for HIV/AIDS. It’s also about how trans people can’t even go outside without the awful and completely realistic fear that they will be obliterated. That the binary world of night and day will burn them to ash, and that hiding in darkness is the only safe option. Or safe-ish, because even those “safe spaces” aren’t as safe for trans people as they are for cis queers (like his coworker Florence, who is a lesbian and transphobic).

Into this slew of terrors comes Elsie, Tracy Britton’s widow and absolute bombshell. Make no mistake: this is a book about vampires, and therefore a very sexy book. Their connection is immediate and electric, but they both struggle to come to grips with their feelings, since Elsie is still grieving her wife and Sol is still grieving his former life. But it turns out that you don’t have to have yourself figured out in order to be loved, or in order to help and love others. You do have to engage, though. You have to be willing to commit things to the record.

The record, though, is a tenuous thing. Sol doesn’t show up in photos, and his presence seems to accelerate the decay of physical materials. His job facilitates the continuance of other people’s stories, but he no longer creates his own. He leaves very few marks on the world. And while he describes the way that deep love and intimacy sometimes create archival black holes, since creators are too busy living to sit around leaving traces of their lives, there is another reason why someone would stop leaving a record: they’re dead.

People infected with vampirism in this world only survive about three years, not because the illness itself but because of their inability to adapt to its demands. They cannot make the transition to an entirely new life with so many new rules. And that’s apt, because Dead Collections is very much about the extent to which transitioning—going from one state to another, whether that’s in terms of gender or aliveness or anything else—does and does not fix what ails you. Sol speaks with piercing ecstasy about the joy of seeing himself as a boy, but he also needs to address the other ways in which he takes up space in the world. He’s settled for less, when he shouldn’t settle for anything less than joy. Elise helps him find some of that joy.

What works: the gender exploration, the take on vampires, the sexiness, the self-reflection

What doesn’t: archival plot a little disconnected until the end

Ideal Reader: Librarians, LGBTQIA+ people, anyone who loves vampires, anyone who loves love

One of Sol and Elise’s first encounters is given in script format, not only an homage to the dead screenwriter who brought them together but also a move by Fellman that urges us to look afresh at the medium of text. What are we reading, and how are we reading it? These are questions that concern Sol as an archivist, and that are touchstones for Fellman as he takes us through Sol’s unique experience of the line between life and death, which turns out to be just as difficult and important and potentially false as gender binary lines. Sol, who once explored his gender identity in forum posts, but who then withdrew from the world, begins to write missives on social media that will change the course of his life, watches his career implode over text, and declares his love in email. His reentry into his own life is chronicled in archivable formats, things he can’t take back.

I hesitate to spoil the ending, but I think it’s also important to say that there is no “kill your queers” in this book. Toward the end, Sol and Else (that’s not a typo) do fall into the archival black hole, producing fewer written records of their relationship. But Fellman very deliberately describes their ongoing conversations about gender as written. They write their identities on a shared whiteboard along with their shopping lists, and even though it’s erased periodically, it is still a record. Sol is once again making an impact on the world, not just with his archival work but with his personal happiness.

The ending is a joy to read, too. The whole book is. Dead Collections is a smart, heartfelt little wonder of a book, and it well deserves a permanent spot in my collections–and yours.