There was a spate of SFF Westerns a year or so ago, but now YA SFF has turned its attention to Russia. We already had the Grisha trilogy by Leigh Bardugo, but with Crooked Kingdom, The Crown’s Fate, and The Bear and the Nightingale there’s a definite trend. And now we have The Five Daughters of the Moon, first in a duo by Leena Likitalo about an alternate universe Russia during the 1917 revolution and fall of the Romanovs.

The Crescent Empire is Russia in almost all but name, a massive northern country with a long history and a convoluted present. Fine horses pull carriages through the streets where new factories rise up, and diamond-skirted nobles dance while the impoverished masses grasp at their hems. Inequality is breeding grave dissent, and there are some who want to take advantage of both worlds. Gagargi Prataslav, the stand-in for Rasputin, is far more devious and wicked than his real-life counterpart. He has built a “thinking machine,” a mechanical nightmare that can predict likely futures and advise courses of action. He wants to use his terrible machine to change the course of the empire, and he doesn’t care that its fuel is a steady

This soul magic is wonderfully done, both sinister and somehow lovely. Likitalo contrasts soul magic and shadow magic, and I am grateful for her decision to withhold any kind of infodump to leave the magic mysterious and thrilling. The extracted souls of animals provide literal illumination, glowing brightly to light the halls of the elites. The moon also shines bright, his magic never quite obvious but never quite dismissable as mere superstition.

The Empress is always the bride of the moon and the mother of his children, although mortal men of her choosing provide the seed. And those men are affectionately called “seed” by their daughters, and embrace this title with joy. It’s a lovely take on a matriarchy. Other details are just as delightful: the fact that the girls choose their own names (a subtle antidote to the patriarchal tendency to give women feminized versions of male names), and choose their own lovers with ceremony but without shame.

This ruling matriarchy soothes my soul, but what about the general population? And what about the secondary characters? All the named generals and soldiers and Gagargi (wizard-priests, essentially) are male, and we know nothing of how the common people structure their homes, although we do see other intimate glimpses of their lives. How is it that the imperial family and the holy scriptures dictate female authority, but the structure of the empire seem to be patriarchal? How is it that menstruation and abortion are still sources of discomfort and secrecy? (Though I am delighted at how the girls’ periods play a not-insignificant role in one of their cunning plans.) It’s admittedly hard to provide all the answers when you’re working with first person POV characters who don’t necessarily question their culture, but I still hope this is explained in the next volume because it’s the only thing that mars my immersion in this shimmering, scintillating world.

The Crescent Empress is just as encased in the glittering oblivion of power as any 19th-century royal of the real world. In her hunger to expand her borders she forgets that she, unlike her heavenly husband, is not unassailable. The cries of the people, who are increasingly burdened by the wars and taxes that fund the imperial style, cannot be shut out forever.

Celestia, the eldest, knows this. Doesn’t she? Or perhaps she is only dreaming. Is she? She can’t remember. Or can she? Celestia, the most rational and responsible of the sisters, has made her first mistake, and it’s big enough to cast all her perfection into doubt. But her nobility–not by birth but by action—makes her an incredibly compelling tragic heroine.

Elise certainly knows, for she has fallen into a romance with a dashing young captain who has secret revolutionary sentiments. Elise is the idealist, dreaming of a bloodless revolution that would leave everyone free to pursue their interests in health and security. Like her immediately younger sister Sibilia, she is naive, but she begins to learn to extract the wisdom of her ideals even when circumstances are not so optimistic.

Sibilia couldn’t care less about the politics, since as the third daughter she is far from both the throne and reality, and dreams away her days in hopes of balls and attractive men. I like that, although Sibilia is a bit clumsy and overeager, she isn’t as ditzy as she first seems. Her combination of naivety and self-indulgence is a product of her circumstances (her wealth and her birth order), but when circumstances call for it, she is also stubborn and brave. Because she exists a great deal in her own little world, her sections are in the form of diaries, talking to herself and gradually finding the strength to understand.

Merile, much like Sibilia, is oblivious to all but one thing, although her focus is her dogs, her “dears” who accompany her everywhere. Again there is a subtle insight going on here: like many young women, Merile is a devoted animal lover, and also a devoted sister to Alina particularly, her youngest and most helpless sister. If she were an ordinary girl, she’d be telling everyone that she wants to be a veterinarian when she grows up. Likitalo is really thinking hard about girlhood and sisterhood, and crafting her characters’ identities not at the expense of the others (all the girls are compassionate to some extent, though it’s Merile’s more defining trait) but in tandem to show us real unity.

And Alina knows much more than any of her sisters, but she’s only six. Everyone believes she is sick, since she is often gripped by fears and visions. But as they dose her into twilight slumbers, they miss her terrible insights: as Celestia calls on the brightness of the moon, Alina calls on its darkness and shadow to grasp things she does not fully understand. Where her power will take the five women can only be guessed.

Can only be guessed—that’s particularly true of this book because it’s daring and imaginative, but also because Tor.com, in its quest to explore the electronic format and publish previously difficult-to-sell short stories and novellas (and kudos for that), has decided that this is going to be two books. For reasons I cannot entirely fathom.

This is the first time that I have seen Tor.com stumble. Why on earth is this a duology? Unless something went really sideways with the publication process, I can’t imagine how a 170-ish page book that ends on a cliffhanger couldn’t have just been delayed to sew the two parts together into one single book of a reasonable length. I mean, I’m all for the shorter formats and the resurgence of the novella, but only if they’re actually novellas, and not bisected novels. Even if the second book jumps radically forward in time or tone, or features different characters entirely, I still think it would have worked better as a single volume.

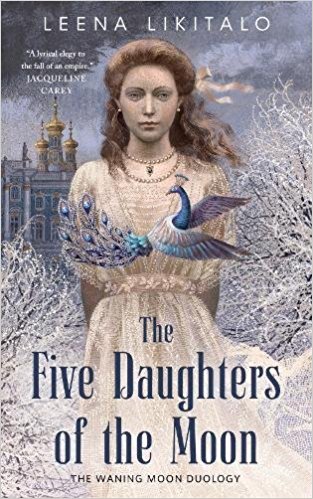

I can’t rightly recommend buying a softcover only to have to shell out for yet another softcover when the next novella comes out (in November! Not even that long!). Better, at least for me and my wallet, to get the ebook–but this is a book I really would like to have a physical copy of, since the cover art really is exquisite. Plus, given the character shifts, it would be nice to be able to flip back and forth between the perspectives.

But enough on the format. The un-novella is still worth a read, even if you do end up gnashing your teeth a bit over the bare four month wait for the next one. I am all keyed up for the concluding installment and the fates of the five sisters and their empire. Celestia, Elise, Sibilia, Merile, and Alina—full, waxing, half, crescent, and dark—are a heavenly combination.

The Five Daughters of the Moon comes out July 25.