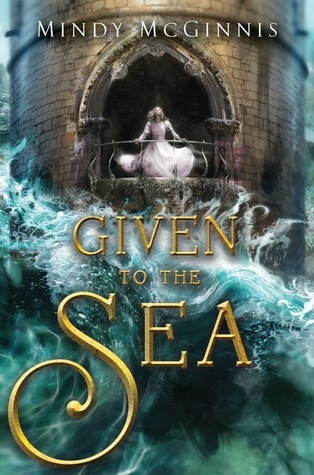

Even though Mindy McGinnis is an accomplished author, this feels very much like a first book. I suppose it’s because Given to the Sea is her first foray into fantasy, a genre divide that strikes some more than others. And it seems to have stricken her as a dramatic one, since that’s the first thing she discusses in her acknowledgements. Having been an avid fantasy reader for much of my life, I think the line is not only blurry but also bullshit—but that’s another discussion. My point is, I think McGinnis psyched herself out a little. She’s trying to tell an incredibly complicated story that features four distinct cultures, four narrators, half a dozen protagonists, and a clash of civilizations that touches on the huge concept of sacrifice. What is worth sacrificing? What is coercive about sacrifice, and when is it too much? What can we ask others to sacrifice and what can we ourselves sacrifice before the whole enterprise is self-defeating instead of self-sustaining?

It’s a fascinating and worthy theme, and McGinnis rightly doesn’t allow us any easy answers. We don’t know if human sacrifice really stops the sea and its beasts from devouring the land, because while the magic of this world is ambiguous, it certainly exists. Likewise we can’t say whether the more subtle sacrifices—of happiness for duty, of romantic love for familial, of self for collective—are worth it, because no one ever knows that. Khosa must throw herself into the sea. Or must the people who love her sacrifice their beliefs in order to save her, when those beliefs might be the only thing protecting an entire nation from ruin? It’s a compelling world full of interesting questions. But in trying to ask them all and get everything just right, it betrays what I think is the author’s hesitance to really push the envelope.

There are entire chapters—short ones! but still—that could have been cut or reworked. I also wonder if this really had to be two books. On the one hand, it’s meticulously plotted to get everyone in exactly the right place for the big finale. On the other, those little details add up like droplets of water eventually filling a cup: slowly. Well, at least it’s a deliberate slowness. McGinnis doesn’t waste time, just takes it, making sure everything is right. And that’s not my favorite, but that’s on me as much as on her. My hope is that things will get snappier and her characters will get better at communicating instead of better at gnawing their fingernails in indecision.

Which—okay. They’re teenagers. They’re just beginning to separate their own desires from others’ expectations and this is a realistic portrait of some fairly natural struggles. Vincent dithers, and Dara is hotheaded. Khosa hesitates and Donil is sure. It’s not that they’re active protagonists or passive ones (God do I think analyses along those lines are limited!), because there is a holistic balance between all of them. It’s more that I expect the situation to intervene if the characters won’t. Encroaching army! Encroaching sea! Magic! Sacrifice! But between moments of dramatic change there are stretches of mundane life.

Maybe that’s the point. Maybe we can see that better now, too, given how politics has become a series of deep, nervous breaths between hyperventilating panic. Life goes on. In some ways, this is a very realistic fantasy! But in other ways it needs to be less realistic and more urgent. There’s a war on, kids, and your intertwined and mutually thwarting affections will have to wait.

That being said, McGinnis’s grasp of tragedy is exquisite. I don’t know if this is an enviable talent to many, but it is to me: I’m so thoroughly impressed by her ability to create relationships and situations that cut to the quick because some fatal flaw makes happiness impossible. Brazenly cheating husbands, parents who abandon children, children who are doomed to die, and all manner of other human wreckage litters the narrative landscape. It represents not only the spectrum of relationships that can warp but also the spectrum of culpability that can be assigned. No one is responsible for natural disasters, and everyone bears at least some crumb of guilt for collective trauma and tragedies arising from tradition. In the middle is individual choice, constrained by both nature and nurture. And the characters stagger from one side of this spectrum to another, trying to inflict the fewest wounds on themselves and others and realizing that there are all kinds of sacrifice.

Donil and Dara, twins who are the last of their race, each wish for a mate. The supreme irony of having a single male and female remain, yet who cannot reproduce is a knife-twisting irony* compounded by their affections for exactly the wrong people of the human race.

The Feneen are the cast-offs of both civilizations, comprised solely of those who survived both their exposure as infants and whatever birth defects led to that exposure. Neither Pietra nor Stille sees much wrong with the practice: this is a place with little science and limited resources. The deformed are mourned, but not too much. Just as the Given, the once-a-generation sacrifice of a young woman who drowns herself in the sea, is not mourned too much. Khosa, the current Given, is malformed in mind just as the Feneen are malformed in body, for she cannot bear human touch.

These people are “broken” and the Stilleans and Pietra are “whole,” at least at first. Silleans are generally affable farmers whose success has made them stagnant. They do not question what may be wrong because so much is right, and thus their superstitions and racism persist. The Pietra are a puritanical culture obsessed with usefulness, who likewise do not question their own failings because their military strength has held firm. However, they are newly made desperate by the twin dangers of an encroaching sea but diminishing catches. The fish have abandoned the lines, and so they abandon their lands in order to take what they cannot earn. Though it’s possible to pity a culture so pushed to the brink that they send anyone who cannot work to the sea as an offering, it’s difficult to empathize. Adding to this is the especially pitiful but bleakly proud Lithos, the man who leads by virtue of his stony heart. He was able to watch everything—everything—he loved offered to the sea as a child and not shed a tear. It makes him hard to hate and hard to love; about all I could manage for him was a distant compassion.

The story is meticulously plotted and not lacking in the many shades of grief and violence that arise from these terrible situations. Nor does it lack in redeeming goodness, the many kinds of bravery and kindness that make individual lives bearable. However, there is precious little levity or hope. McGinnis is great with threat and implication, and great with no-win scenarios, and that’s both her triumph and her Achilles’ heel: it’s hard to see a way out of this perfect web, and hard to root for characters whose happiness comes at other characters’ expense.

The endings for all the individual characters are bittersweet if not downright bitter. (Of course, there’s a second book, so there’s a chance this will All Work Out for the Best.) But the endings for the various peoples and cultures are strangely hopeful. We see the Pietra softening to the idea of becoming dependent on and possible more equal with the Stilleans, and becoming downright impressed with the Feneen. At least some of the Silleans want to protect the Given from the sea instead of toss her in it. And Donil and Dara have had their whole lives to reconcile themselves to the diminishment or abnegation of their way of life for their children, who may or may not have any of their gifts.

Uncomfortably but not unrealistically, most of this compromise and softening of cultural boundaries has to do with sex, and much of it is not consensual. The Pietra perpetuate atrocities off screen, rapes and encounters with unequal power dynamics that the Lithos predicts will lead to a mingling of their cultures before too long. He’s not wrong, either. Reproduction is a means of controlling culture as well as controlling people. Relationships are also fettered or fed by power, another unsettling reminder that even for the most innocent there is more at stake than love or lust.

And the women always come off worse. Princess Dissa watches her husband’s infidelities without hope or recourse. Dara is regularly sexually harassed. What Khosa endures is a slight intensification of what most women feel all their lives: that someday, there will be a man who wants her, and probably not even her but what she represents—as if she’s some abstraction as well as just some body—and he will rape her. Because the Given, by tradition, needs to bear a child before she dies, and it doesn’t much matter whose. Each of the women copes and fights back in her own way, and comes away with victories as well as wounds. But these victories are all reactions. There is relief in them, but no joy. I hope that in the conclusion we are able to see the protagonists, and especially the women, begin to act for things instead of just against them, making real and active choices.

I am eager to see what happens, but I hope the pace for the next book is faster and the characters’ entanglements more forgiving. This is such a first book that it really hangs on the next installment, and I want McGinnis to pull it off.

*okay, yes, even if you had one male and one female of a species then their kids—siblings—would have to reproduce and it would get traumatizing and inbred real fast. We are talking about literary tragedy, not biological.