Angels are tricky. They’re not like vampires or werewolves (obviously): their motivations are opaque, and their weaknesses are practically nonexistent. They make poor monsters as a result, and even poorer heroes, prone to perfection as they are. Even worse, they’re often portrayed as extensions of a greater force; it’s not even clear if they have free will.

Fallen angels are more superficially approachable, but to me are even more difficult to get right. Take all that perfection and give it a fatal flaw, one worthy of the worst punishment imaginable: it’s a study in extremes that humans are, by many definitions, not even able to comprehend. How do you express that majesty and ruination? And how do you locate yourself relative to Blake and Milton, let alone the Bible and the Qur’an?

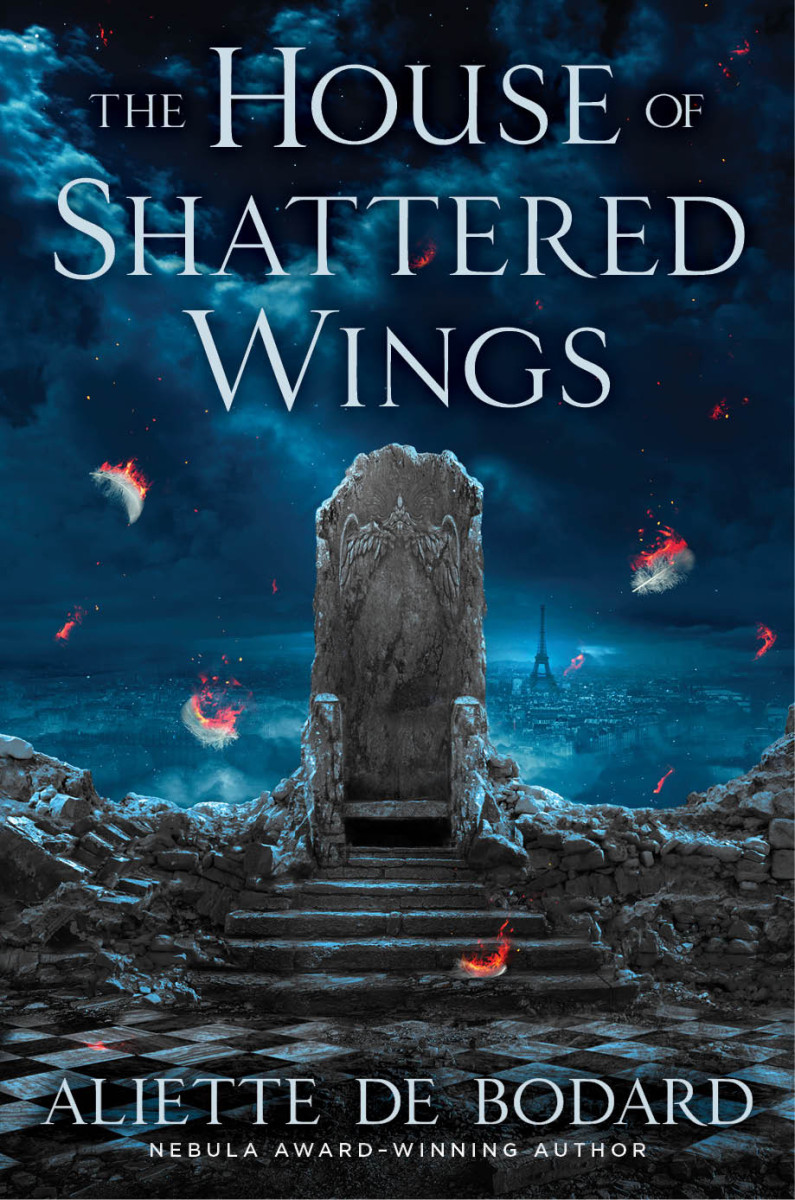

Location is actually a good place to start. The House of Shattered Wings decides on Paris, the City of Light, but a ruined and decidedly un-romantic version. It’s just after the Great War, though in this world WWI was fought with magic and captained by angels, and the poisons of the trenches have lingered much longer. The city is a blasted shell of its former self, as are its inhabitants who grope for scraps of power in the wreckage. One such scrabbler is Philippe, a man with a much longer past than his looks suggest. There are elements of Roger Zelazny’s and Jane Lindskold’s Lord Demon, though Philippe lacks the rakish charm typical to Zelazny’s heroes. He’s darker, quieter, more haunted. He’s not precisely human, but he’s not a Fallen either. His uniqueness is reason enough for the Fallen to capture him and study him, but they also catch him in a moment of greed: he is discovered while harvesting flesh from the (still-living) body of a newly Fallen, tasting her blood and the power it contains.

Location is actually a good place to start. The House of Shattered Wings decides on Paris, the City of Light, but a ruined and decidedly un-romantic version. It’s just after the Great War, though in this world WWI was fought with magic and captained by angels, and the poisons of the trenches have lingered much longer. The city is a blasted shell of its former self, as are its inhabitants who grope for scraps of power in the wreckage. One such scrabbler is Philippe, a man with a much longer past than his looks suggest. There are elements of Roger Zelazny’s and Jane Lindskold’s Lord Demon, though Philippe lacks the rakish charm typical to Zelazny’s heroes. He’s darker, quieter, more haunted. He’s not precisely human, but he’s not a Fallen either. His uniqueness is reason enough for the Fallen to capture him and study him, but they also catch him in a moment of greed: he is discovered while harvesting flesh from the (still-living) body of a newly Fallen, tasting her blood and the power it contains.

Philippe isn’t a vampire, merely an immortal of another sort; but all creatures, including other Fallen, crave even the slightest pieces of angelic bodies, which are imbued with power. This moderately damning activity does not impede a tentative friendship between Philippe and the new Fallen, Isabelle. I would have liked to see more than obligation and blood bind them, but all the characters are too suspicious to spend quality time with one another. They exist in a world where power is nearly all that matters, especially because it’s in such short supply. Magic is scarce, and trust scarcer. Fragile alliances criss-cross the city and the great Houses, ready to break or re-align at the slightest hint of change, and change is certainly brewing.

The bleak, broken Paris is still waiting for word of Morningstar, greatest of the Fallen, who disappeared decades ago without a word or sign. He left Selene in charge of his House, but she is not the master tactician he was, and has brought the House on hard times. Philippe and Isabel find themselves confronting weakness as well as strength, and plain ignorance as well as malice. So often authors go to great lengths to explain and explain, and have their characters be the best and the wisest; it’s refreshing and, I think a mark of skill, to find a world more realistically shaded with such potent absence. Certainly it adds to the generalized air of decay de Bodard describes. Interestingly, it doesn’t make the tone depressing, but heightens both the narrative tension and the sense of place. The world, like the Fallen, are shadows of themselves, and beset by yet more shadows both metaphorical and literal.

The shadows that Philippe and Isabel unwittingly unleash have the potential to bring about the fall of Morningstar’s House. Mystery and violence swiftly unfurl, but not the kind of mystery you can solve if you’re clever enough. All the clues aren’t there, and the culprits seem either a little obvious or far too obscure to guess. But I don’t really mind. Much as I like a well-crafted mystery, this isn’t supposed to be an episode of CSI. The mystery resides in how the characters respond to their limited choices, wringing nobility and yes, a little faith, out of bad and worse options.

This book runs into a common pitfall in tone that many authors struggle with: it lacks a sense of humor. In trying to create a serious world with serious issues, de Bodard risks a certain homogeneity in her characters by making them all fairly humorless. I’m not saying the characters have to be a laugh a minute; not a single one has to crack a joke, so long as there’s at least some acknowledgement of some of the fundamental ironies in the situations she’s created. There are angels and priests struggling to believe in a God they know must be real, and a former ascetic bound by an obligation of stolen flesh, and no one gets a grin out of it. Humor is one of the ways we cope, and it’s also a way of creating breaks in the tension. Even tension can be monotonous. While The House of Shattered Wings doesn’t descend into that, ratcheting up the mysteries and punctuating the narrative with action to break things up, it does totter on the edge from time to time.

***Note to Biblical Scholars and Theology Enthusiasts:***

There is a fantastic Bible joke early on if you know what you’re looking for: Oris says that he’s found evidence that “adelphos” means “brother” and not “cousin.” Actually, “adelphos” does mean brother. The issue comes from Mark 6:3 and Matthew 13:55, which refer to the “adelphos” of Jesus. This could imply that the Virgin Mary was no longer a virgin if, you know, she had other kids (Mary’s perpetual virginity is important to some). Hence many Christian scholars trying to make “adelphos” mean cousin. Apparently they succeeded. Having an ex-Angel puzzle this out is extra-hilarious. This is, however, a laugh for the maybe 20 people who read Greek and have a background in theology, and my point about humor still stands.

***End Scholarly Nerding***

Because de Bodard chose this sub-genre, I feel it’s necessary to point out several issues that go along with it. First of all, although she does an admirable job of contending with an absent and potentially indifferent God, there is no mention of Jesus or the wider presence of the church. It’s not surprising. These elements make things infinitely more complex from a thematic and theological standpoint, and also run an even higher risk of offending readers. But since de Bodard has characters mention the New Testament and even attend Catholic mass, it becomes a more glaring omission. There needs to be more engagement with the deeper roots of the Christian mythos, just as there is with the mythos of Vietnam.

Second, two of the major Fallen characters, Selene and Asmodeus, are in same-sex relationships. There’s no overt issue here, both relationships are handled with appropriate complexity, depth, and individuality. However, given the current relationship between Christianity and homosexuality, it’s hard to avoid thinking about the broader implications. I’m not saying de Bodard is equating homosexuality with sin–she makes it clear at the start that angels lack gender before they fall. This is merely an observation that there is some very boggy territory here, and more conversations about the theology of it all would have been welcome. Such conversations would have fleshed out the world of the Fallen as well.

It is, as ever, barely a criticism to want more from a book. I could easily have enjoyed another hundred pages or so of detail about Paris, about some of the characters, and about the underlying mythologies. I dearly hope that de Bodard will return to this world and its characters, since she can do more with less–with the diminished, the lost, and the dispossessed–than many others have in their far more typical dystopias. It is an admirable addition to the difficult subgenre of angelology, and one that deserves a wide audience.

House of Shattered Wings will be available August 18, 2015