Like many people during this pandemic, I’ve been in a bit of a reading funk. A bit of a doing-anything-at-all funk, if I’m being honest. I lose interest in things quickly, if I do them at all. I can’t read more than a few pages. I do the dishes in stages. Heck, I got up in the middle of that last sentence to brew my fifth cup of tea this morning.

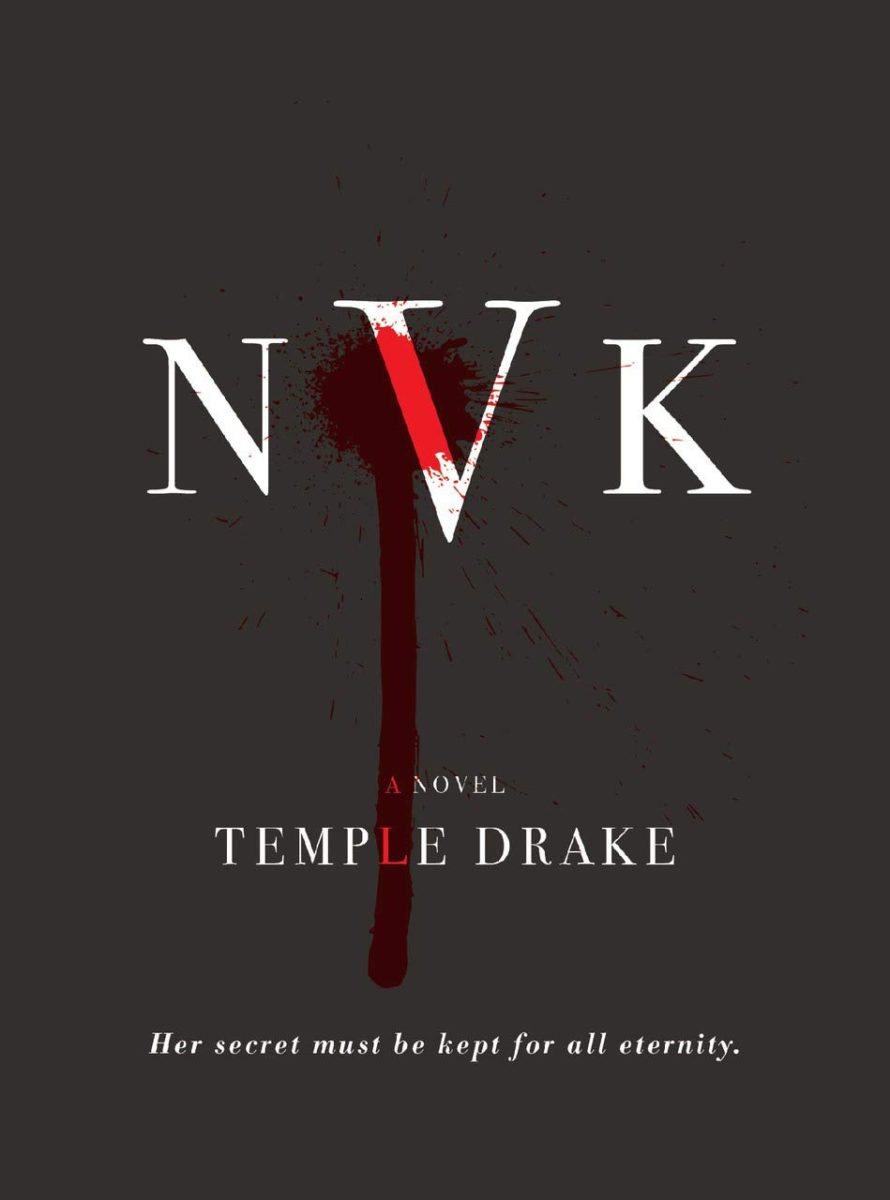

NVK got me out of that funk for a little while. It’s a fascinating book even if it’s an imperfect one, and it asks a lot of interesting questions about vampires, about ghosts, and about the true origins of what we consider monstrous.

On the surface, this book wants to be Crazy Rich Asians with vampires. Which is bonkers, but the fun and interesting kind of bonkers. The 1% of the 1% in Shanghai with their personal drivers and their glamorous parties is quite Money Pop, and adding in vampires—clearly the most chic of all the monsters—is delicious. It’s fun to hear about nightclubs and the luxury suites being visited by a woman so glamorous she’s not even human anymore. (And hey, there’s a nice commentary in there about the inhumanity of wealth.)

But what the book cares more and more about as it goes on are the supernatural elements of the story. Which is not an inherently good or bad thing—I like both these things. But Drake is torn even more between telling a creepy horror-esque story about Zhang’s dangerous liaison with a vampire, and telling the story from Naemi’s perspective, which is much more of a straightforward personal history.

The issue is that NVK never really decides which direction it wants to go and tries to have it all. It gets muddled by the repeated emphasis on the finer things: are we meant to care about Zhang’s inner life, or the flashy outer life with all his $2,000 suits? The inner and the outer don’t really meld very well, making the reading experience a bit more like whiplash than deliberate contrast. It feels like Zhang should just have been a normal musician, not a mogul who’s also a rocker who’s also an expert in Chinese pottery who’s also a chivalric defender of women who’s also …you get it. Zhang’s a little too perfect. It makes all the drama surrounding him feel a little contrived, since he’s not actually the source of any real conflict: the conflict with his sister’s boyfriend, the shady investment deal, the dubious motives of his friends.

The only conflict he has is with Naemi, whom he treats with exquisite courtesy but apparently too much interest. As he tries to get to know her, he begins to find strange inconsistencies in her stories and finds odd features of her life. Why does she never seem to sleep? Why does she never eat?

His friend Mad Dog seems to have the answers. “She wants justice or retribution. She cannot rest,” he warns Zhang (190). He’s an expert on Chinese ghosts, but is that really what Naemi is? And is vengeance actually what she wants? Certainly she’s not consciously seeking it. Far from it: she wants peace. She wants to be safe. But her past has taught her that no one and nothing is truly safe forever.

“For a ghost, time is nonlinear. The present isn’t a development of the past, but a palimpsest through which the past continues to assert itself” (194). This is a brilliant line and a compelling take on the nature of ghosts. It’s also a great take on any long-lived creature, vampires or witches or whatever Naemi actually is. That the past, and specifically past trauma, could be the source of such intense power that the usual rules of time and longevity break down is a great foundation for supernatural happenings.

I’m torn, because the chapters about Naemi’s past were my absolute favorites. They were urgent and moving, and they gave us strong emotional ties. But they also disrupted the uncertain atmosphere of Zhang’s story. Zhang gradually comes to understand there’s something strange going on, but we already know that. There’s some interesting friction between what he thinks he knows—that Naemi is some kind of vengeful spirit—and what is actually true—that Naemi is a different supernatural entity entirely.

There’s a very interesting theoretical component to this book: that the cultural lenses through which we view things never allow us to fully see or articulate those things. All lenses—even the ones that clarify some things—ultimately distort. Mad Dog can only see Naemi through the lens of his education, and specifically his deep learning on the topic of Chinese ghosts. He fits her into the categories he already knows, and then makes assumptions based on those categories. But his theories are wrong because Chinese ghosts are culturally specific. (As are Western ghosts. As are all ghosts, as is the category “ghost”, etc. etc.) Naemi is something else. But what?

We don’t know because she doesn’t know. Naemi can’t even see herself properly, because she lost her a huge part of her culture when she lost her family. She’s also so far removed from her people in time as well as in space that she has become a foreigner.

The idea of “foreigner” or “foreignness” is persistent throughout the text, since Naemi is white, blonde, and from what is now Finland, but fluent in Mandarin and living in Shanghai. For many readers, both of these locations will feel “foreign,” as will the level of extreme wealth. This sense of remove from the characters actually makes both Naemi and Zhang Other, to us and to each other. Monsters are the ultimate Other, and NVK is really getting back to the roots of that other-ness by de-familiarizing them.

As with the category of ghosts, NVK calls into question the category of vampires. The alterations Drake makes to the basic tenants of vampirism made me think long and hard about the underlying nature of vampirism. There are a lot of books now with sympathetic vampires, ones who turn only the willing or prey only on the wicked. But writ large, vampires are born from violence, and sexualized violence at that. Victims often do not consent—and are then changed into creatures who inflict the same violence on others. This mirrors what we know of abuse, in which the abused in many instances go on to abuse others.

But Naemi doesn’t feed on others, only on herself. Auto-vampirism makes a lot of sense from a coping perspective. Naemi’s strange power comes in part from the violence inflicted on her family. Internalizing the pain and turning it to a kind of supernatural self-harm, rather than inflicting harm on others, is yet another common coping mechanism we see in real-life abuse cases. I’m surprised this hasn’t come up before but extremely glad Drake has introduced the concept.

The theoretical and historical elements are perfect. The present-day story, though, less so. There simply weren’t a lot of stakes for Naemi in Shanghai. What would have happened if she were discovered? Well, she’d have to move. Probably. But would she be arrested? No. She didn’t actually commit any crimes. Or would she be captured? No again: there was no supernatural hunters or bigger, badder witches or vampires after her. The worst possibility for her was having to break off a relationship she enjoyed. And despite her declaration of love—which just felt odd, not romantic or tragic—I didn’t get the impression that this was going to strongly impact her life. She hadn’t had any desperation to connect with people, and there wasn’t any life-altering despair at having to leave them behind. She didn’t change.

Zhang didn’t change much either. The end of Zhang’s story felt a bit tacked on, an ending with finality just so the story could be over. I will say that it did add to Naemi’s legend, though: her story is one of ill-luck, but also of uncertainty. Is she a harbinger of bad things, or is that just life, with hers so much longer than most?

Ultimately, the book never fully explains what Naemi is. Which is fine, since we have enough words already to talk about her: ghost, vampire, witch, and more, each category made unstable and imperfect by Naemi’s challenges to our assumptions about them.