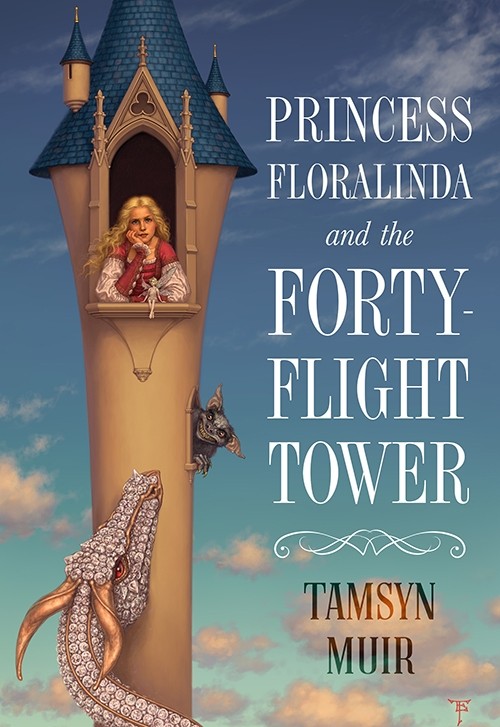

It’s no secret that we here at Geekly love Tamsyn Muir and her gothic sensibilities. But does her necromantic space opera mean that she can write a fantasy-based fairy tale as well?

Of course it does. Duh. Muir is brilliant in a way that has already transcended genres. Why wouldn’t she be able to pull off a fairy tale? Princess Floralinda and the Forty-Flight Tower is another triumph of storytelling. It’s punchy, smart, and occasionally gory, a welcome addition to the fairy tale retelling genre.

But, well…is it a fairytale? Well, it has a fairy in it. And a princess. And a tower, a dragon, and some princes. Definitely it has those. Not in the right order, though. And not with the usual message. Not even with the unusual message that’s quite popular in re-writes, about princesses being rebellious and Not Like the Other Girls. Floralinda is like other girls, and specifically like other princesses. She wants to be. She’s quite content being as beautiful as sunlight atop water, and just as shallow. But what she wants doesn’t matter. Not unless she makes it matter.

That’s the first cruel lesson, but there are many more to come. Floralinda has been taken to the top of a tower to wait for a prince, but the princes keep dying on level one. It becomes clear that she’s not worth the risk, but that doesn’t mean she can just walk away. She’s forty flights up. Winter is approaching. No one is coming to save her. What can she, an expert in embroidery and polite conversation, do if she wants to keep on living—and will she recognize her life if she keeps adapting to the changes?

Through deprivation, neglect, violence, and danger, she learns a good many lessons about how life works outside the prescribed narrative structures. Is it grim? Yes. Is it Grimm? Er—well, that depends. It definitely has a moralizing narrator, but the morals are not your usual sort. Instead of learning to be Good and Kind, or having those virtues rewarded, Floralinda learns the opposite. Her abandonment in the tower teaches her cruelty, violence, and pain, both the experience of it and the infliction of it upon others.

Muir uses Floralinda to explore the permanence of change and the capriciousness of “adventure.” Experience defeats innocence, and innocence does not come back. Experience is less of an evolution and more of a consolation prize here, a motley collection of knowledge and instinct that keeps Floralinda alive but definitely not comfortable. In other stories, becoming a warrior seems awesome and shiny, a nice trade-up from docility. Here, it’s gross and wrenching and only slightly better than being dead. The ruination of sweetness is no victory here. There is not much joy in hard-won wisdom—not much, but enough.

It’s not uplifting. But neither is it depressing. It’s very much a lemonade from lemons sort of book (maybe orange juice is a better metaphor here, but oh well), its message not sweet, but palatable all the same.

Though you may wince to swallow its lessons, the act of reading it is a pure delight. Its grimmest moments tip over into humor, and its lightness conceals dark twists. It’s a book to keep you guessing and on your toes, a thrilling, spiraling descent. It’s a descent into the underworld of fairy tales, the shadow-place where fairy-tale rules find their most extreme—but natural—conclusions.