I admit that I’m not a big fan of short story collections. I’m thrown off by the wild jumps in setting, narrative voice, and theme, so I tend to only read three or four stories before getting distracted by a novel. My exception is for collections of interlocking stories, set in the same world, dealing with the same themes and sometimes even the same characters. I always enjoy finding these collections, since they have the wide-ranging creativity of other books of short stories, but the focus and sustained complexity of standard novels.

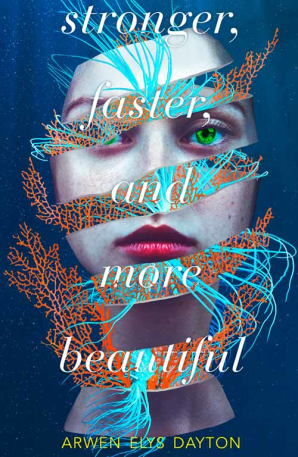

Stronger, Faster, and More Beautiful by Arwen Elys Dayton is an intriguing collection of just such interlocking tales, all of them having to do with biomedical advancement as it affects humanity. That sounds rather dry, so let me emphasize that there are also religious cults, genehacked children who are part dolphin, and teens who can survive on asteroid mines in deep space. But the point isn’t to shock. It’s to explore lives that have been fundamentally altered in ways that straightforward science could never have predicted.

I wouldn’t say the stories really push into new thematic territory. I’ve seen all of the topics explored before, and I don’t know that Stronger, Faster, and More Beautiful asks new questions or gives new answers for any of them.

Instead, the stories shine because of their particularity. They focus exclusively on teenagers, and especially on individual teens. These stories, in other words, aren’t just thought exercises: none of the stories could be told without their specific protagonists. Milla and Jake and Luck and all the others make this book real, and that gives all the attendant questions so much more depth and tension.

The message of compassion is not unexpected but also not unwelcome. Particularity helps with this overall theme, since it’s easy to think of these issues in broad strokes and make judgments, but harder when individuals and all their messy needs and wants are on display.

The stories are also comfortable with complication and don’t make too many sweeping claims about the necessity or advisability of any particular modifications. What it really cares about is how those modifications impact lives, and what each person chooses to do with that altered life. Most of the characters can’t help the changes that have been wrought upon them; they can only muddle through adapting to those changes and finding new ways to live and thrive.

I would have liked to see more investigation of consent: what it means when you’re hurt, or when you’re a child, or when the politics of your country have changed. It’s there in the background, always implied but never fully engaged. Alexios from “Eight Waded” never consented to the experimental modifications that caused him to be born with an overlarge head and stunted limbs, but how could he? And did that make his nominal consent to further modifications (really, it was his parents who had to agree) less meaningful, or more? Jake obviously didn’t consent to his extensive modifications, and Milla obviously did, and defends her lifesaving modifications against zealots and bullies. The contrast is implied, but making it more explicit would have helped tease out some of the larger issues.

If you like science fiction and want a diverting YA read, this is a good choice. It’s also a perfect book for travel, since the stories lend themselves to reading in distinct segments. Each story is distinct but of equal quality, not too heavy, and will give you things to think about even after all of them are done.