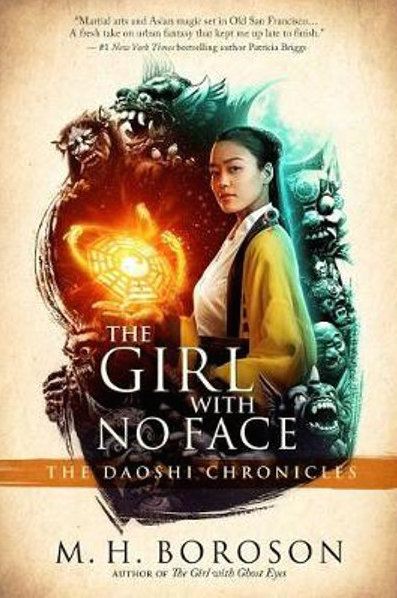

It’s been a while since we heard from M. H. Boroson, but his debut The Girl with the Ghost Eyes made such a strong impression that I had no issues jumping back into what is now a planned trilogy. His alternate universe San Francisco is a magical place, and I was beyond excited to resume the story of Li-lin, the girl able to see the spirit realm overlaid on the mortal world.

Li-lin may be that titular girl with ghost eyes from the first book, but she only metaphorically lacks a face in this second installment. Disowned in the first book for disobeying her father, she now works as a bodyguard and spiritual protector for one of Chinatown’s gangs. She is proud of her work and skilled at it, but she has been in a holding pattern since the events of the last book.

Your face is, obviously, what you show to the world. But it’s so much more than that. It’s your dignity, your credibility, your social standing. It’s even your history. Just as you can see a parent’s features passed down on a child’s face, you can reference a complex web of relationships when mentioning “face.” Conversely, to deny someone face is to hide them, shame them. A person with no face is a person with no place in the community.

This is why, when Li-lin encounters a girl who literally has no face (just a blank span of flesh), she feels compelled to act. Li-lin knows what’s it’s like to be denied face. As a woman in a patriarchal society, as a young person, and as a Chinese person in a racist and xenophobic nation, she chafes at the limitations and does not want another girl to suffer the same.

It’s not just the faceless girl who needs her, though. She’s sworn to protect not just her gang’s boss, but his little daughter as well. And then there’s the matter of a girl who was recently killed in a way she cannot begin to understand: strangled from the inside out by a strange flowering plant. In China, masters would guide disciples and parents would guide children to the answers, all of them in their right place. But in America, everything is topsy-turvy. Girls have no faces, no lineages, and some even have no families—the deceased girl is a paper wife. How can Li-lin be faithful to her cherished traditions and also fight for those who tradition has abandoned?

“Paper” relatives refer to people who were not related (or not closely related) except on paper; which is to say, on official government documents. In order to get around (racist, fear mongering) immigration policies, immigrants would claim to be parents, children, husbands, wives, and siblings of Chinese people already living in the country.

Here’s an important piece of history you might not have learned in school: Chinese immigrants were the first to be targeted by legislation limiting immigration from a specific ethnic group and nation. Chinese women were the first to be targeted: in 1875, America forbade any and all Chinese women from immigrating to the US. Then Chinese Exclusion Act of 1882 forbade any immigration from China, and banned all Chinese immigrants already in the country from ever attaining citizenship. These racist and xenophobic policies were then compounded by other injustices at the state and local level in the form of additional taxation, quarantines, and harassment.

Just in case you thought this shit was new.

But let’s leave relevant political and historical parallels aside and get back to The Girl with No Face’s other excellent traits and insights. I can see the origins of some of the action in HK and Taiwanese cinema, but Boroson has a flair of his own. At one point, Li-Lin skewers one enemy and, without pausing to remove her sword from that enemy, goes right on to stab another. It’s over the top in the best way. It’s also fun. Grimdark is all very well, but it’s nice to read something that embraces the spectacular possibilities of the format and the story.

The battle sequences combine well with the magic, too. There are big, showy magics full of danger, and also small, subtle magics full of cleverness. And, not to be outdone, there are maneuverings that are not magic at all, just sound magic theory and legal reasoning based on Daoist principles. I wholeheartedly adore a good technicality. Legal argumentation, done right, can be just as thrilling and devastating as a physical or magical fight, and I’m glad to see Boroson is continuing to excel in this area as well.

The feminist threads of the story are powerful and affecting. Boroson clearly put as much thought into reflecting on Asian American women’s issues as he did into his Daosit research, and it shows. Li-lin has some powerful conversations with her father about the imbalanced nature of their relationship, but those conversations are tempered by love and respect. I think it would have been easy for this to turn into a preachy, black-and-white series of diatribes, but instead there’s nuance and care.

One particular sequence also really impressed me with its feminist critique of a fantasy trope I hate: the love potion. It’s not actually that common anymore, thankfully, but until The Girl with No Face I hadn’t seen too many takedowns of the idea. Li-lin, though, demolishes the idea that a love potion can be anything other than a circumvention of consent and a ruinous disrespect for someone’s personhood. When she is ensnared—but not fully caught—by a love spell, she pours all her spiritual and physical power into a bid for escape, never once dismissing the threat to her autonomy.

This scene reminded me of several points in Harry Potter that involve love potions. It was deeply uncomfortable even when Romilda secretly tried to force a love potion on Harry (despite being written with a slightly humorous tone), and downright criminal when Tom Riddle’s mother enslaved his father with repeated doses. The books are already a product of their time, the pre-#MeToo era, and it’s not my goal to further castigate Rowling. Rather, I want to point out how far we’ve come that love spells have gone from plot devices and jokes to objects of horror and catalysts for discussions about consent.

The ending feels a bit unearned on a purely narrative level. Emotionally, Li-Lin’s progress and that of many other characters makes complete sense. There’s a moving realization for both Li-lin and her father, a heartfelt release of trauma, and so on. But the mechanics of her final stratagem were not sufficiently explained or foreshadowed, making the ending feel a bit like a deus ex machina.

Still, that’s more of a quibble and not a full-blown complaint. The flaws in the ending don’t detract from my overall impression of the book, which is that it’s a worthy follow-up to The Girl with the Ghost Eyes and a wonderful adventure on its own terms.

The Girl with No Face comes out October 8th.