Reading The Last Dreamwalker is like slowly easing yourself into a hot bath of bittersweet and magical family strife; as you slide deeper, the old secrets, new connections, and ever-present hurts slip up across your lips, into your nose, filling your ears with their muffling warmth and your eyes with their sting. It’s languorous—if you crave fast action and breakneck thrillers, The Last Dreamwalker won’t be your cup of tea. But if you seek complicated and painful legacies, fraught family ties, and a seeping tide of quiet horror leavened by love and camaraderie, this book will fill you up and let you steep in it.

It’s been a while since I last read something like this. The first stories I reach for as comparisons are two inspired responses to Lovecraft’s work, The Ballad of Black Tom by Victor LaValle and The Dream-Quest of Vellitt Boe by Kij Johnson. But while The Last Dreamwalker shares some of the dreamy, atmospheric, and often painful wanderings of those books, it draws from a different well of inspiration. Moreover, it doesn’t need any comparison to HPL and all his ugly baggage. The Last Dreamwalker blurs the edges of reality and cultivates lingering dread, but it has compassion for its all-too-human monsters and complicates its seemingly crisp moral distinctions. Through that, this story dives deep into the uncomfortable connections between self-determination and isolation, and the long-lasting scars inflicted while fighting for a family legacy.

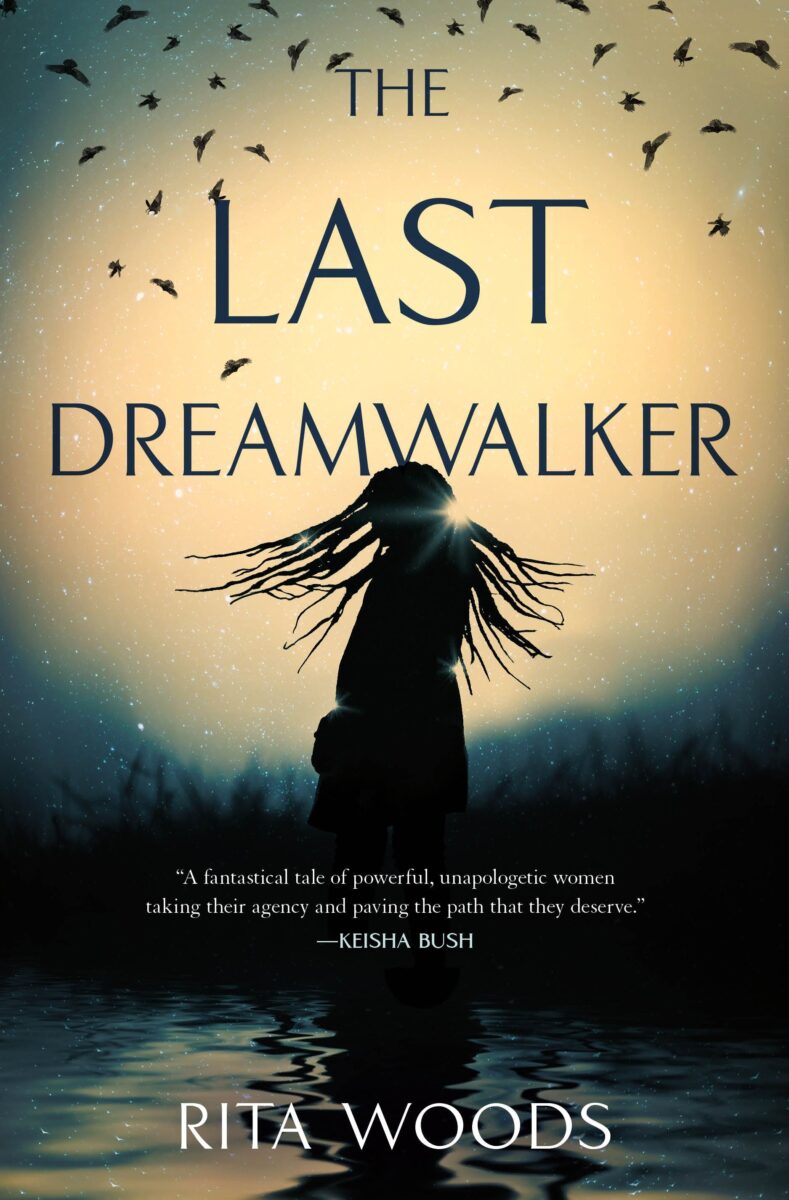

Set partly in D.C., partly along South Carolina’s coast in the Gullah-Geechee region, The Last Dreamwalker is driven by inheritance and legacy, both good and bad. With the death of Layla’s mother, previously well-buried secrets bubble to the surface. Layla’s attempts to reconcile the cold and judgmental woman she knew with the conflicting stories she uncovers—and the very real deed to an island with her name on it—draw her into old and painful strife. Her efforts to make sense of this, and to find a way through the Gordian knot of her family’s past without losing her mind or her life, propel the story.

A brief aside for the unfamiliar: Gullah-Geechee (sometimes simply Gullah or Geechee) is a creole language spoken predominantly by people of color along the South Eastern Atlantic Seaboard, and can also refer to these people as an ethnic and cultural group. As a language, it arose during slavery from the combination of many different African language traditions with English. This creole and the isolation of coastal and island plantations on the South Eastern Atlantic Seaboard (from southern North Carolina to northern Florida) gave rise to a distinct local cultural and language tradition which continues to this day. For more information, follow this link.

With The Last Dreamwalker, Rita Woods has tapped into the agonizing intergenerational struggle inside a family, the pain of inheriting old and hidden traumas, and the ways familial bonds twist and bind. She’s portrayed—neatly and well—the push and pull of connection between those who both love and (perhaps) hate each other. And she’s melded all that conflict and connection and alienation into something palpable and mysterious, the power of dreamwalking, a shared inheritance tying the generations together across their beautiful, uncomfortable, and frightening dreamscapes.

As a storyteller, this book inspired me. I admired the slow and dreadful creep of tension and the bleed between reality and unreality. Woods’ use of two narrators, one past (Gemma) and one present (Layla), lent more than depth and historical context to the story; it also planted the seeds offostered my fears for Layla, laying bare the danger to dreamwalkers unmoored between their waking and sleeping worlds and the threat dreamwalkers can pose to others.

As a fan of horror, I delighted in the burgeoning sense of threat, and the way the warping of one’s own dreams could render uncanny the reassurance of home and the familiar. I want to conjure the same unease in my own work—to slowly strip away characters’ feeling of safety, as Woods does, and give them an uncomfortably intimate view of the people who scare them most. Woods peels back the layers around her “monster” and shows us the human inside without making them any less frightening. It’s excellent.

And as a human being, I appreciated the painful complications and uncertainties our narrator revealed with each successive layer of secrets she uncovered. People are messy and complicated, and their lives no less so—coming to terms with that messiness, understanding people for all that they have been and now are, is one of storytelling’s gifts. Woods shares that gift here.

If you’re looking for adrenaline-junkie drama and thrills, I suggest browsing elsewhere. But if any of the above sounded good to you—if you want a touching horror story oozing with painful familial weight—I absolutely recommend The Last Dreamwalker.

The Last Dreamwalker will be available September 20, 2022.