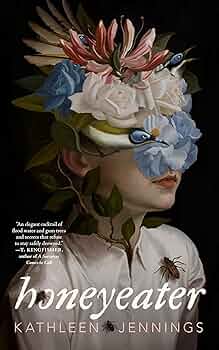

There are certain settings that present a higher difficulty level for authors. Not that it’s easy to write a book even when the setting lends its heft to the narrative, but an old Victorian house looming behind iron gates for a horror story or a glittering high-rise for a locked room mystery certainly do some work. And then there’s Honeyeater, a gorgeous new novel from Kathleen Jennings, which sets an atmospheric, fantastical horror story in…the suburbs?

Yes, it’s possible, and yes, it’s wonderful. Given Jennings’ previous splendors, specifically the novella Flyaway, I would like to say “no surprise there,” but I was delighted to find that there is surprise here, too. I did not expect so much of it.

The setting is a major source of that surprise. A suburb is meant to be the best of both the urban and rural worlds. In reality, it’s a compromise verging instead on the worst of both, the green spaces too often manicured out of wildness, the moderate density breeding distrust and homogeneity rather than community. Jennings’ now-glittering, now-shadowy prose inverts the suburb and makes it seem possible to be that better version of itself, not harmless but therefore not neutered either. There is real beauty in the furious resistance of nature to the taming impulse of domesticity, and real menace, too.

In such a deceptively safe place is the Wren house, Number 21, which is now home to siblings Charlie and Cora Wren after the death of their aunt. Charlie is back to handle his aunt’s effect, returning again to the town he can’t ever seem to truly leave. He’s tried many times, but there’s a gravity to Bellworth. Or, at least that’s the convenient answer. Charlie is also a bit aimless and a bit feckless, so is his lack of drive something to be blamed on his family home, or on himself?

But crashing into this malaise of ennui comes Grace, a tangled construct of vines and disconnected memories that has wrenched free of the creek to walk, unsteadily, into the world. Grace is full of undirected fury, and wants to know why she’s achieved her unsteady consciousness. Her only ally seems to be Charlie, who knows little but might end up risking much. Charlie, and “the taxi driver’s daughter,” a girl whose absence of a name marks her very firmly as not part of the founding families of the town. What do these outsiders, by birth or by action or both, have in common? What can they even accomplish here?

Jennings definitely excels at atmosphere, and the book is amazingly, almost relentlessly atmospheria. It made me want to visit an Australian suburb, which is not a thing I thought I’d ever say. The beauty of individual flowers and overall landscapes is vivid, darkly splendid.

This was a very—very—contained narrative, and sometimes that became a little stifling. The action, whether physical struggles or investigation into the mysteries, barely left the confines of Bellworth, and in fact almost never left the confines of Number 21. There’s a certain interest in that, a density. It does feel intentional. But the clues themselves feel incidental, and any progress toward solving a mystery that itself is uncertain feels vague. This meant that Number 21 didn’t feel like a true haunted house, but instead more like a house with a haunting. Or rather, hauntings plural, a veritable infestation of ghosts. The house itself is not an agent of malice. If anything, it feels like another victim.

And that is an interesting effect, but I also didn’t know enough about the house, narratively speaking, to really root for it. It’s also not clear that the house’s existence is in any way threatened—it’s just the inhabitants who are in danger, and even that isn’t certain. Really, it’s just Grace, the strange interloper, and maybe the taxi driver’s daughter.

Or at least, they’re the ones in danger in this story. But there are lots of other stories of suburban threat, the legends that permeate every aspect of the landscape, from root to branch and bug to bird. These microfictions interspersed between the chapters are excellent, really top-notch understanding of what urban legends are (and aren’t). They’re not too over the top, but they do make the neighborhood seem awash in magic and danger. I only wish that the tellers of these tales, imagined from the prologue to be sitting around swapping stories during a flood, would have played a greater role in the main narrative. They never appear as meaningfully distinct characters, only as a kind of distant chorus. This lends the book a kind of eerie instability, the sense that the neighborhood is populated by impressions as much as people—more ghosts, if you will.

I’m enjoying the recent trend toward more unusual hauntings, notably The Haunting of Velkwood, which expand what is possible with ghosts and ghost stories. No longer contained to houses and darkness, the sun-drenched echoes of ambiguity, rather than singular lurid crimes, are making the ghost story interesting again. Jennings’ boundary-pushing Honeyeater is another excellent example that I have no doubt will push the entire subject and genre forward.

Honeyeatercomes out September 2nd, 2025.