Welcome back to Magic Gatherings!

Earlier this week I dropped a shorter article about building a Commander deck around Oath of the Gatewatch‘s [mtg_card]General Tazri[/mtg_card]. But I’m back again (tell a friend) with a much longer and more different article, this one about limited, in celebration of this week’s Magic Online flashback draft format: triple Champions of Kamigawa.

Few blocks are as polarizing for Magic fans as Kamigawa. Coming on the heels of the original Mirrodin block, which almost broke the game with the affinity mechanic, Kamigawa was noticeably, albeit necessarily, lower in power. Its janky cards were and are the subject of ridicule by a good portion of the playerbase, and its distinct flavor was off-putting for some. Meanwhile, R&D has since concluded that its mechanics were too parasitic—that is to say, Kamigawa cards only play well with other Kamigawa cards. (As we’ll see, Spirit tribal is a big part of Kamigawa’s mechanical structure, but people tend to miss that Ravnica picked up on those tribal elements pretty well.)

Kamigawa block wasn’t a very successful block, by Magic standards. And yet, there are those who love it. They’re most notably seen ceaselessly plaguing Mark Rosewater with questions about when, if ever, we’ll see a Return to Kamigawa block.

I love Kamigawa block. It will always have a special place in my heart—it’s the block that got me back into Magic for good. So today I’m going to talk about Kamigawa’s history and flavor, with a bonus analysis of the set as a limited format.

The History of Kamigawa

But let’s start with that distinct flavor. Champions of Kamigawa was the first block to do something that’s since become common in Magic design: take a flavorful real-world source material as a muse, then design a top-down set around that source material and its tropes. All the mechanics, creatures, art—everything was designed to reflect Kamigawa’s inspiration, Japanese mythology and folk tales. Essentially, Kamigawa is the “flavor block” in the same way that Mirrodin was the “artifact block,” Onslaught was the “tribal block” and Odyssey was the “graveyard block.” The same approach (slightly refined) has produced some of the most popular blocks Magic has ever had, including Theros and Innistrad. But Kamigawa pioneered it.

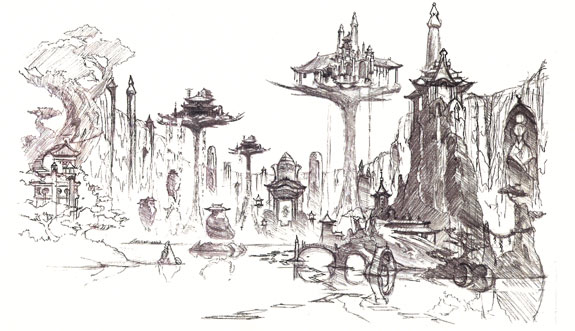

Kamigawa Island concept art.

In the conceiving the plane, Magic‘s creative team went far, far out of its way to represent Japanese mythology sensitively and respectfully, an impressive effort when you consider how syncretistic that source material is in the first place. Japanese folk tales are filled with mercurial spirits and fantastic creatures, any of which may be helpful or harmful (maybe both) to the people who encounter them. Eventually, guided in part by creative properties like the films of Hayao Miyazaki (whose Spirited Away and Princess Mononoke really capture the alternately wondrous and dangerous aspects of Japanese spirits), the creative team hit on the idea of a plane at war with its own spirits, its own kami—the tiny gods that personify each and every object. The kami were enraged with the plane’s mortal populace, who had to defend themselves against angry gods in their most monstrous, wrathful aspects.

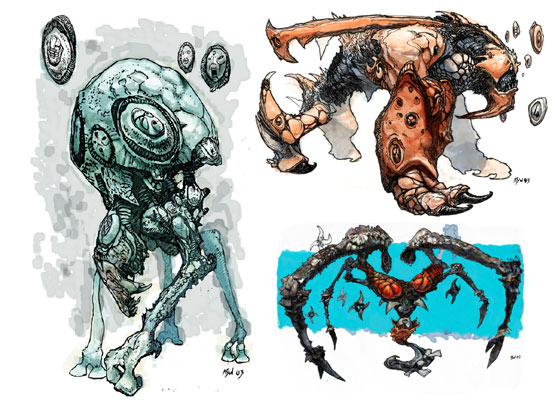

Kamigawa’s Spirit creatures are wonderfully unlike anything else we’ve seen: barely comprehensible amalgamations of thought and form, at once compelling and horrifying. These are gods in the oldest sense, who demarcate the “sacred” as being ineffably but irrefutably other from our normal, mundane world. We worship them because they are beyond our ken; they speak to something different from us and greater than us, which nevertheless reminds us of the ultimately unknowable deep corners of ourselves.

Kamigawa’s Spirit creatures are wonderfully unlike anything else we’ve seen: barely comprehensible amalgamations of thought and form, at once compelling and horrifying. These are gods in the oldest sense, who demarcate the “sacred” as being ineffably but irrefutably other from our normal, mundane world. We worship them because they are beyond our ken; they speak to something different from us and greater than us, which nevertheless reminds us of the ultimately unknowable deep corners of ourselves.

Spirit concept art.

In other words, this is a bold and profound artistic choice—strange for a card game, maybe, but then maybe not so much for a game that has five distinct philosophical perspectives baked into its design.

The mortal side of the war is contested by Kamigawa’s legendary heroes, which form another pillar of the block’s mechanical design—”Legendary matters.” Every rare creature in the block is Legendary—perhaps too subtle, but it did great work for suggesting a massive, rich world filled with dynamic stories. Some of these legends played major roles in the story ([mtg_card]Konda, Lord of Eiganjo[/mtg_card]; [mtg_card]Sensei Hisoka[/mtg_card]); others form a colorful backdrop that beckons to the imagination. They even had flip cards, which evoked the set’s themes of transformation by showing a hero’s journey in miniature.

Beyond the legends themselves, Kamigawa is populated with some of the most unique and interesting nonhuman races Magic has ever created. There’s the honorable kitsune (foxfolk), the filthy nezumi (ratfolk) and the reclusive soratami (mookfolk, who cleverly have rabbit-like ears—in Japan there’s a rabbit in the moon, not a man in the moon).

Beyond the legends themselves, Kamigawa is populated with some of the most unique and interesting nonhuman races Magic has ever created. There’s the honorable kitsune (foxfolk), the filthy nezumi (ratfolk) and the reclusive soratami (mookfolk, who cleverly have rabbit-like ears—in Japan there’s a rabbit in the moon, not a man in the moon).

Soratami concept art.

The world and the story are described through some of Magic‘s best flavor text. Most notably, the creative team returned to the trope of quoting fictional historical documents (Great Battles of Kamigawa, Observations of the Kami War, The History of Kamigawa), which hearkens back to the days of Fallen Empires and its Sarpadian Empires quotes; they lends a sense of gravitas to the flavor text.  But there are also glimpses of the personal, as well—letters between major characters, journal excepts from anonymous monks. The flavor texts hint, rather than describe, and the process of coming to understand the major events of the story inductively mirrors the sense of uncovering ancient lore.

But there are also glimpses of the personal, as well—letters between major characters, journal excepts from anonymous monks. The flavor texts hint, rather than describe, and the process of coming to understand the major events of the story inductively mirrors the sense of uncovering ancient lore.

All of this is expressed through Magic‘s mechanics and flavor itself; in a way, Magic itself is the palette used to paint Kamigawa for the player. The end result is a plane that is starkly, entirely its own. Kamigawa isn’t merely a backdrop for a card game about magical spells, nor is it just a riff on Japanese folk religion—it’s a creative achievement unto itself, which could only emerge from the combination of the two.

The party line from Wizards is that Kamigawa block was an attempt at top-down, flavor-first design that failed because the tropes of Japanese mythology just weren’t resonant for most Americans; no one knew what Wizards were referencing, and their riffs were too bizarre and alien. To the contrary, I would argue that Kamigawa is one of the bravest worlds Magic has attempted—a classic example of how real-world inspiration can be adapted into a unique and original setting. Does everyone like it? No. But when you worry about making a world that everyone likes, you’ll never make a world that anyone loves.

Returning to Kamigawa

For me, Kamigawa happened at exactly the right time, when I was at exactly the right place in my life. I’ve mentioned before that I got into Magic around Fourth Edition. In high school, I took a hiatus; I was a little too willing to fold to peer pressure. Towards the end of my freshman year of college, my then-girlfriend’s younger brother started talking up Mirrodin, the current set at the time. I was pretty impressed with how original the cards were—stuff like [mtg_card]Platinum Angel [/mtg_card]and [mtg_card]Mindslaver[/mtg_card], that did things I never imagined Magic cards could do.

When I got back to college in the fall, I joined the nerdy co-ed frat on campus. One of the members had a boyfriend who’d just graduated, moved cross-country, and taken a job in town while she finished her senior year. He had time and disposable income, so he started organizing drafts in the house. To prepare, I checked out the preview articles, which had even more exciting cards. A 2/2 for W? End the turn? They resonated with the new cultural concepts I was encountering for the first time and beginning to explore—I saw Spirited Away just before my freshman year as was busy working through the Miyazaki oeuvre. And tone, the names, and the flavor text of the cards brought back the sense of wonder from Ice Age and Fallen Empires, some of the first sets I played.

Kamigawa reflected what I remembered of Magic from the past, but also the new person I was becoming. Themes of transformation, indeed. And that, friends, is how I got back into Magic for good.

Mechanic Dynamics

Of course, I was just getting back into the game, and I won’t lie—I was awful. (I still am awful, just slightly less so.) So in addition to walking down memory lane, drafting Champions of Kamigawa again gives me the opportunity to re-evaluate the set’s limited play, with the benefit of twelve years of experience.

First up: mechanics.

- Spiritcraft—Ironically, the set’s backbone mechanic wasn’t even named at all. “Spiritcraft” is player shorthand for the wealth of Spirit creature abilities that trigger “whenever you play a Spirit or Arcane spell.” Today, this would be represented with a catchword (an “ability word”) like Landfall. Spiritcraft is a tribal mechanic through and through, rewarding you for playing more and more Spirits and spirit magic; the “spirit magic” aspect, in particular, set the stage for the heavy tribal elements in Lorwyn two years later. Spiritcraft synergies aren’t not worth playing garbage cards in your deck to trigger ([mtg_card]Wandering Ones[/mtg_card]), but it’s fine to take a Spirit over a non-Spirit that’s slightly stronger, in the abstract.

- Soulshift—Another Spirit mechanic, albeit one that’s slightly less restrictive, soulshift was meant to evoke the changing and enduring nature of the kami—when it seemed they had been defeated, they merely morphed into a different form. When a Spirit with soulshift dies, you can return another Spirit creature card with lower converted mana cost from your graveyard to your hand. Soulshift only shows up on Spirits and only lets you retrieve Spirits, but you often have a reasonable chance of getting a card back even if your deck isn’t especially Spirit-focused. On the other hand, you can also build elaborate “soulshift chains” where your six-drop gets back your five-drop, which gets back your four-drop, and so on. When you consider that these decks will often have profitable spiritcraft triggers like [mtg_card]Thief of Hope[/mtg_card], you get a sense for how grindy and resilient dedicated Spirit decks can be. Soulshift shows up in white, black, and green.

- Splice—The last Spirit mechanic, splice allows players to build their own haymakers by tacking on additional effects to their spells. When you play an Arcane spell, the game gives you an opportunity to splice extra effects on: you reveal the card you’re splicing and pay its splice cost, but the card itself stays in your hand. In other words, [mtg_card]Glacial Ray[/mtg_card] can add a 2-damage rider to each and every Arcane spell you cast. This presents some interesting choices in drafting and deckbuilding, as you need to balance strong splice cards with the base arcane spells that make them work. Splice shows up in all colors, but especially in blue and red.

- Bushido—Compared to Spirits, the other side of the Kami War isn’t as well-defined. The most notable mechanic is bushido, which turns up on Samurai creatures in white, red, and black. It gives a boost to the creature’s stats during combat. In spite of being a simple, clean mechanic, bushido looks underwhelming on the cards, particularly since creatures with the ability look a little undersized for their costs—which is further exacerbated by the fact that creatures from Kamigawa just aren’t as big as we tend to see these days. But, as I’ll discuss below, power and toughness values in this set are tightly clustered, so a modest bushido bonus matters more than it might appear. As a result, bushido can help creatures go unblocked or trade up.

- Flip Cards—These crazy-looking uncommons and rares are the forebears to Innistrad‘s double-faced cards: creatures that enter play in one form, then “flip” in the course of play to a second, more powerful form. I have a soft spot for these, in spite of their confusing layout; I love cards that offer players a chance to go on a “quest,” with a clear goal and a clear reward, and the flip cards really capture the flavor of epic characters who rise from humble beginnings to become world-shaking legends. Unfortunately, in limited, these tend to be traps, as most have flip conditions that require too many contortions to be worth it. The best have starting sides that are already reasonable because of their stats ([mtg_card]Nezumi Graverobber[/mtg_card], [mtg_card]Budoka Gardner[/mtg_card]) or because they have powerful activated abilities ([mtg_card]Jushi Apprentice[/mtg_card], [mtg_card]Nezumi Shortfang[/mtg_card]). Much as I loved [mtg_card]Bushi Tenderfoot[/mtg_card] back in the day, I can’t recommend him now.

General Impressions

Mechanics only tell part of the story of a limited environment, though. How does the Champions of Kamigawa limited play out as a whole?

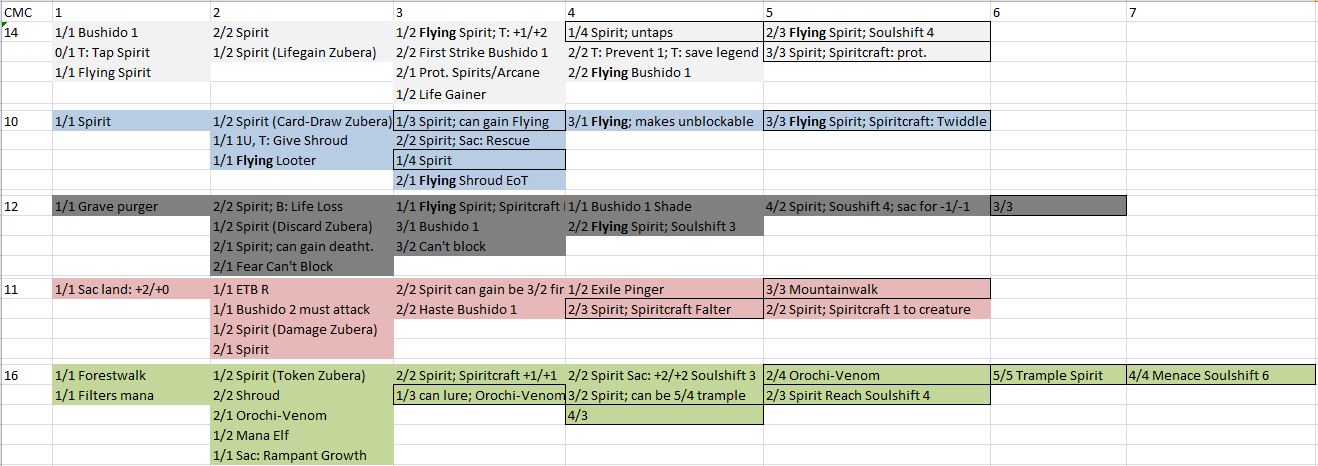

Creature sizing—I mentioned above that creatures in Kamigawa are quite a bit smaller than what we see these days. Oath of the Gatewatch, for example, has 3/2 creatures for three mana in three different colors. Kamigawa, on the other hand—well, you might as well take a look.

That table (click for a larger version) has the power and toughness scores of all the common creatures in Champions of Kamigawa. As you can see, 2/2 is the most characteristic power/toughness combo. The average power is 1.81, and the average toughness is 1.96. That’s not a big differential, which would normally suggest the format’s speed would be fast-to-medium—but because the creatures are so small on average, they usually won’t deal enough damage to opponents to close out the game quickly. An uncontested [mtg_card]Nezumi Cutthroat[/mtg_card] is a much slower clock than, say, an uncontested [mtg_card]Kor Castigator[/mtg_card].

On the other hand, creature sizes also don’t range as large as they do in recent sets. In Oath of the Gatewatch, green gets a 5/4 for five mana in [mtg_card]Tajuru Pathwarden[/mtg_card] and red gets a 4/4 for five in [mtg_card]Cinder Hellion[/mtg_card]. 3/3 for five is a tough guy in Kamigawa, and a 1/4 like [mtg_card]River Kaijin[/mtg_card] can block almost everything. [mtg_card]Moss Kami[/mtg_card] rules the format as a 5/5 trampler for six. That means smaller creatures don’t get as outclassed as they normally would—a [mtg_card]Dripping Tongue Zubera[/mtg_card] can take down a [mtg_card]Sokenzan Bruiser[/mtg_card] with a little help from [mtg_card]Kodama’s Might[/mtg_card].

The close clustering of powers and toughnesses also shows why bushido can be pretty relevant—even a bonus of +1/+1 can make a creature almost impossible to block profitably. [mtg_card]Kitsune Blademaster[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Ronin Houndmaster[/mtg_card] trade or beat just about anything in the format, let alone near their mana costs.

Power level—All this makes it sound like Kamigawa’s creatures are miserably underpowered, and that its limited games are a boring slog decided by weak cards. While it’s true that the power level is a bit low, there definitely is power in the set—it just tends to be concentrated in a few cards.

Power level—All this makes it sound like Kamigawa’s creatures are miserably underpowered, and that its limited games are a boring slog decided by weak cards. While it’s true that the power level is a bit low, there definitely is power in the set—it just tends to be concentrated in a few cards.

Take [mtg_card]Frostwielder[/mtg_card], for instance. Not only can she pick off about a third of the common creatures in the set, or send a point per turn to the opponent’s head if she doesn’t have anything to murder, the narrow power/toughness band in the set means she makes all your two-power creatures nearly impossible to block, since they’ll all trade up easily with your opponent’s three-toughness blockers. Two Frostwielders on the battlefield at the same time should clean up most any boardstate in a hurry.

By the same turn, [mtg_card]Kabuto Moth[/mtg_card] is one of the best commons in the set. The +1/+2 bonus looks humble, but in the context of the set it’s a dramatic jump—suddenly your two-drop brawls like a five-drop.

Repeatable, board-dominating effects like these are not things Wizards puts at common anymore, because they make your opponents’ lives miserable. There are other goodies, too, relics of a different era in Magic design. [mtg_card]Sokenzan Bruiser[/mtg_card], for instance—landwalk doesn’t get used anymore, but here it’s on a sizeable creature that can randomly be unblockable, just because your opponent happens to also be playing red. Or take [mtg_card]Befoul[/mtg_card], one of the best removal spells in the set, which can also randomly manascrew your opponent if that happens to be useful.

Removal—Speaking of removal: it’s a little less dense than it tends to be in modern sets, so you need to prioritize it. In particular, white and blue have just one removal spell, and green has none at all. What spells are there do perform well—[mtg_card]Befoul[/mtg_card], [mtg_card]Rend Spirit[/mtg_card], and [mtg_card]Rend Flesh[/mtg_card] are all pretty attractive, and [mtg_card]Cage of Hands[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Mystic Restraints[/mtg_card] are all-purpose enchantment removal. [mtg_card]Yamabushi’s Flame[/mtg_card] is a step up from [mtg_card]Touch of the Void[/mtg_card], and performs even better given that Kamigawa doesn’t stretch up to seven- and eight-drops.

Color Notes

All of that preamble should give enough context for evaluating cards on the fly as you draft. Still, I wanted to make some summary comments about each color:

- White—White’s best common is the unassuming [mtg_card]Kabuto Moth[/mtg_card]. As I mentioned above, the bonus it provides is extremely relevant, given the sizing of creatures in this set; just the threat of it makes blocking decisions difficult for your opponent. White’s common removal spell is [mtg_card]Cage of Hands[/mtg_card], a [mtg_card]Pacifism[/mtg_card] with the option to re-buy for a more threatening creature. [mtg_card]Kitsune Blademaster[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Mothrider Samurai[/mtg_card] are its best creatures, but [mtg_card]Kami of the Painted Road[/mtg_card] is pretty serviceable, if you can trigger it reliably. At uncommon, [mtg_card]Nagao, Bound By Honor[/mtg_card] is a real bomb, [mtg_card]Innocence Kami[/mtg_card] is better than it looks, and [mtg_card]Samurai Enforcers[/mtg_card] can tussle with pretty much anything.

- Blue—Blue has a lot of “air” at common in this set, thanks especially to the trifecta of [mtg_card]Reach Through Mists[/mtg_card], [mtg_card]Peer Through Depths[/mtg_card], and [mtg_card]Sift Through Sands[/mtg_card]. Those spells make good grist for splice, though, and [mtg_card]Callous Deceiver[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]River Kaijin[/mtg_card] support a defensive, long-game plan that maximizes card advantage. [mtg_card]Teller of Tales[/mtg_card] is a great finisher there. Blue’s Moonfolk creatures all fly, generally have low toughness, and all have spell-like abilities activated by returning lands to your hand. The first activation usually won’t set you back too much, but later ones require careful management. At uncommon there’s the famous [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card] and many more flyers.

- Black—Black has the best aggressive offerings at common, with a couple three-power three-drops to back up the excellent [mtg_card]Nezumi Cutthroat[/mtg_card]. [mtg_card]Wicked Akuba[/mtg_card] looks attractive, but usually needs help to get through—try [mtg_card]Kami of the Waning Moon[/mtg_card], in a pinch. [mtg_card]Devouring Greed[/mtg_card] can be an excellent finisher. Don’t be scared by the conditional targeting on [mtg_card]Rend Spirit[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Rend Flesh[/mtg_card]—almost every deck will have a creature worth killing. At uncommon, there’s tons of power: hefty demons, [mtg_card]Thief of Hope[/mtg_card], a legit sweeper in [mtg_card]Hideous Laughter[/mtg_card], and an effective [mtg_card]Overrun[/mtg_card] in [mtg_card]Dance of Shadows[/mtg_card].

- Red—As I mentioned above, [mtg_card]Yamabushi’s Flame[/mtg_card] is the premier removal spell of the set, and [mtg_card]Frostwielder[/mtg_card] is a potentially board-dominating common. [mtg_card]Glacial Ray[/mtg_card] is also excellent. [mtg_card]Ronin Houndmaster[/mtg_card]’s stats look unimpressive at first blush, but it runs through most blockers at its spot on the curve. [mtg_card]Kami of Fire’s Roar[/mtg_card] can also do good work; given how clumped creature sizing is, [mtg_card]Falter[/mtg_card]ing a single creature can really mess with your opponent’s blocks. [mtg_card]Hearth Kami[/mtg_card] is a better aggressive creature than [mtg_card]Battle-Mad Ronin[/mtg_card]. [mtg_card]Uncontrollable Aggression[/mtg_card] is a tough sell with all the unconditional removal running around, but +2/+2 is a pretty serious buff in this set. At uncommon, [mtg_card]Blind with Anger[/mtg_card] is the big star—instant-speed [mtg_card]Threaten[/mtg_card] usually costs more.

- Green—Green’s in a rough spot; since Kamigawa is pre-fight, it doesn’t have any removal, so it has to rely on raw size (read: [mtg_card]Moss Kami[/mtg_card]) and tricks like [mtg_card]Kodama’s Might[/mtg_card] to win games. There are tools for ramping, with [mtg_card]Orochi Sustainer[/mtg_card], [mtg_card]Sakura-Tribe Elder[/mtg_card], and [mtg_card]Kodama’s Reach[/mtg_card]. [mtg_card]Kami of the Hunt[/mtg_card] is sized well for the format, if you’re activating spiritcraft every turn, and [mtg_card]Burr Grafter[/mtg_card] is similarly great in theory, but it’s hard to base a Spirit deck in green. At uncommon, [mtg_card]Strength of Cedars[/mtg_card] is excellent, and cards like [mtg_card]Sosuke, Son of Seshiro[/mtg_card] come at good rates. [mtg_card]Kashi-Tribe Reaver[/mtg_card] is pretty resilient, and [mtg_card]Hana Kami[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Honden of Life’s Web[/mtg_card] can give some lategame power.

The Dampen Thought Deck

No Kamigawa limited review would be complete without mentioning this gem. While modern Magic sets have lots of draft archetypes seeded into them, back in the day it was much more likely that successful draft decks were piles of good cards that all promoted the same general strategy: aggressive or defensive. Kamigawa had a literal game-changer in the [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card] deck. It’s hard to overstate the importance of [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card]—the idea it pioneered, that cards ignored by all other drafters could be cobbled together into a winning archetype, has informed the best-loved and most deeply textured draft formats in Magic’s history.

The deck is essentially an ultra-defensive splice deck, usually white-blue. A few defensive creatures ([mtg_card]River Kaijin[/mtg_card], [mtg_card]Harsh Deceiver[/mtg_card]) hold the ground, and the rest of the deck consists of every Arcane spell that can prevent damage or otherwise delay the game. [mtg_card]Peer through Depths[/mtg_card] and [mtg_card]Eerie Procession[/mtg_card] find the namesake card; then it’s splicing, turn after turn. Attack me? [mtg_card]Ethereal Haze[/mtg_card], splice [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card]. Again? [mtg_card]Candle’s Glow[/mtg_card], splice [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card]. [mtg_card]Consuming Vortex[/mtg_card], splice [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card]. [mtg_card]Reach Through Mists[/mtg_card], splice [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card]. [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card] splice [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card]. You get the idea. For reference, six or seven [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card]s should mill out most opponents, so splice accordingly.

What made the strategy so powerful and so interesting was that it used cards very few other drafters were interested in. [mtg_card]Eerie Procession[/mtg_card] is not a card for most decks, but for the [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card] drafter it’s an invaluable tutor they can find with an eleventh or twelfth pick. If the secret’s out, it’s risky: there’s no guarantee a given pod will even open a [mtg_card]Dampen Thought[/mtg_card], and the archetype can’t support two players. But if you see pieces of the deck start to wheel, move on in and get ready for a fun draft.

TL; DR

Look, this is a long article, so I won’t blame you if you just flipped here first. (You should read the rest, though; I promise it’s good.) To summarize, and to make a few points that didn’t fit anywhere else:

- The creatures in Champions draft are weaker than you’re used to, but they’re closely sized relative to each other. 3 and 4 toughness are large numbers. Bushido and combat tricks matter. 2/2s for 3 and 2/2 flyers for 4 are all fine deals.

- Evasion is important. Be prepared to clock your opponent with a 2/1 fear or a 3/3 flyer.

- Removal is important; what’s there is effective, but there’s not a lot of it.

- Be open to splashing, especially for removal spells. There is practically no manafixing, but running three Mountain to cast two [mtg_card]Yamabushi’s Flame[/mtg_card] is totally reasonable.

- Most colors have few commons that are dramatically more powerful than the rest.

- The uncommon Honden cycle are all pretty good, even if you only have one in play. If you get two at once, they’ll take over the game quickly.

- Games tend to go longer, so card advantage like soulshift (and even [mtg_card]Counsel of the Soratami[/mtg_card]) matters.

I’ve been looking forward to flashback Champions of Kamigawa drafts for a while now, so I hope you enjoyed this trip down memory lane with me. Flashback drafts will continue all year, so if you liked this article be sure to let me know (in the comments, or tweet @cutefuzzy_), and I can reprise with subsequent formats. I’ve been playing Magic for a while and I have a lot of memories.

Its hard to Love Kamigawa, as it was them moving on from the huge story and characters I grew up playing magic with. I recognize that the set still has value as I play commander a lot now, but I cant feel nostalgia because of the disinterest when it came out.

Nice article.

While I’m aware of the issues Kamigawa had, and I can see why many players didn’t like it…. I will admit that it’s still my favorite MTG expansion ever.

I played a few more expansions after Kamigawa and Ravnice (the expansion I liked the most aside from Kamigawa), but I eventually got tired of the game and quit a few years ago, I recently had a look at what subsequent sets had to offer, but none of them even remotely impressed me. To be honest, it won’t happen but a return to Kamigawa would be the only thing that would push me to play the game again.

A couple of comments about why it is still, by far (except for Ravnica) my favorite.

Flavor and Art

Most players were not familiar with Japanese lore, but I’ve always been interested in Japan and this theme matched many of my interests.

Also, while most sets are just bland, generic rehashes of generic themes, Kamigawa really was very different from any other sets, and its mechanics and art clearly reflected that.

MTG is justly famous for using high quality art, but most sets are pretty similar to each other, and the art, at best, is a bland representation of what geeks that have spent most of their life in front of computers, and know or care nothing for foreign cultures or real lore, imagine. I don’t blame WOC for it, it’s what sells, but that doesn’t change the fact that the Japanese inspired art of Kamigawa was more unique and memorable than the art of most sets, as it really made an effort to give the set a completely different feel compared to other expansions.

Mechanics + Limited

Well, I can see why some were not popular (not powerful enough and didn’t work well with other sets)…. but they were rather original and, partly because of the lower power of the set, really rewarded clever play (or design in constructed) rather than luck of the draw.

Furthermore, ninjutsu is probably one of the most interesting magic mechanics ever used and really captured the flavor of blue (trickery at its finest, cards going into play and coming back to your hand etc)

My old UB ninja deck was the most fun I’ve ever played with (and actually competed a lot better than you’d expect against much more famous archetypes, in pretty much any format at the time).

The only UB deck that even came close in terms of fun was a Faery deck I used later on, although it became a little too mainstream to be really fun (lots of mirror matches in tournaments)

Power

One last comment. It’s true that the set didn’t interact well with other expansions (too much of an emphasis on arcane and spirits was, imo, the design team’s biggest mistake), but it still provided a lot of strong cards and accurate statistics I saw a couple of years later showed that it contributed as many good cards to strong archetypes as most other sets did (mainly rares, though, and it did lack more universally used commons in wider ranging formats)

as I said it won’t happen, but one can dream……. bring back kamigawa, WOC!